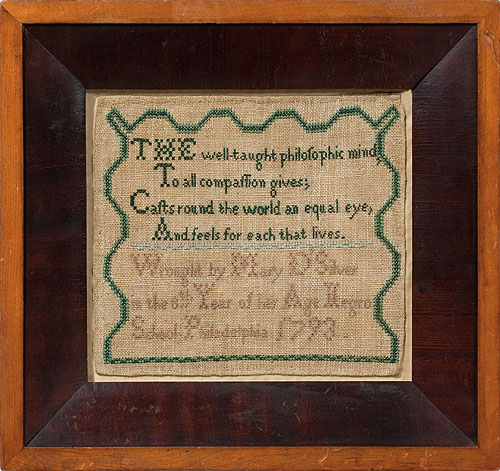

Mary D’Silver, Negro School, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1793

Documented samplers made by African American schoolgirls are extremely rare and we are privileged to offer this outstanding example, a recent discovery and the only 18th century sampler known to have been worked at an African American school. The maker, Mary D’Silver, was “in the 8th Year of her Age” when she made this sampler and was attending a Philadelphia school with a fascinating history. A small sampler, it was executed with very fine needlework and remained unframed for 220 years; it is indeed remarkable that it survived. It adds substantially to the body of knowledge of African American samplers and the education girls of color received in Federal Philadelphia.

Philadelphia contained the first large population of free Blacks in the colonies. By the 1780s and 1790s, slightly more than 2000 people of color lived in the city; less than 1% of this population, thanks to Pennsylvania’s Gradual Abolition Act of 1780, was still enslaved. If any 18th century sampler made by an African American girl was to surface, it is understandable that it would be from Philadelphia.

In her inscription, Mary stitched the words, “Negro School Philadelphia.” There were actually three different schools that used this designation in the last decade of the 18th century (one was the well-known school for Blacks established by Anthony Benezet). Evidence strongly suggests that Mary attended the Negro School administered by the Bray Associates, a London-based organization founded by Dr. Thomas Bray (1658-1730). This Anglican cleric promoted education and religious conversion among slaves and free Blacks in the colonies starting in 1724. By the 1750s, the Bray Associates looked to Benjamin Franklin for assistance in establishing formal schools in the colonies and Franklin’s enthusiastic response led to the funding and opening of four schools dedicated to Black children in Philadelphia, the first of which opened in 1758. The Associates opened similar schools elsewhere in the American colonies in the same period, notably in Williamsburg, Virginia, New York City and Newport, Rhode Island. With Franklin at the helm, the Philadelphia schools were considered a great success. Contemporary accounts confirm that the curriculum of these Negro Schools included instruction in sewing, knitting and embroidery.

While the Revolutionary War forced the closing of four Bray Associates schools in Philadelphia, one subsequently was reopened. Franklin remained in charge of this school until his death in 1790. Succeeding Franklin as school head was the Reverend William White (1748-1836), the long-term rector of Christ Church in Philadelphia. According to church archives, Emanuel D’Silver and Judith Jones were married at Christ Church by the Rev. White in 1783. Also, according to church archives, Rev. White baptized the one-year-old “Mary Desylvas” (spelling of the surname varies) “Daughter of Emanuel & Judith Desylvus – Negroes” on September 24, 1786.

White was also integral to the establishment, in 1798, of the first African American Episcopal Church in the United States, the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas. Judith D’Silver, Mary’s mother, was buried in St. Thomas’s cemetery after her death in 1808. These intersections and affiliations between Rev. White and the D’Silver family strongly suggest that Mary D’Silver attended the Bray Associates Negro School and worked this sampler there in 1793.

The verse Mary stitched on her sampler is also important and keenly relevant to the ongoing discourse about African American freedom. Written by the English poet, Anna Letitia Aikin Barbauld (1743-1825), it is the seventh stanza from her twelve-stanza poem, The Mouse’s Petition, originally published in 1773. A highly regarded social reformer and abolitionist, Barbauld’s poem was written from the perspective of a trapped mouse attempting to appeal to his captor’s “philosophic mind” and “compassion.” This metaphor, of course, speaks to the plight of enslaved Africans and their relationship to slaveholders. The stitching of a thoughtful and poignant argument for freedom by a young samplermaker is an important departure from the traditional poetry usually found on period schoolgirl samplers. Interestingly, young Mary D’Silver, or her teacher, changed one meaningful word in the final line of Barbauld’s stanza. Here, “And feels for all that lives” becomes more personal and individual as “And feels for each that lives.”

The sampler was worked in silk on linen and is in excellent condition. It has been conservation mounted and is in a 19th century frame.

Sampler size: 8” x 8¾” Framed size: 12¾” x 13½”

This sampler is from our archives and has been sold.