Spotlight: In-Depth Dive into Noteworthy Needlework

From time to time, we post in-depth studies of significant samplers, or groups of samplers

Mission Samplers from Sierra Leone:

Traces of a Black Woman’s Career in the Church Missionary Society, c.1811 to 1841

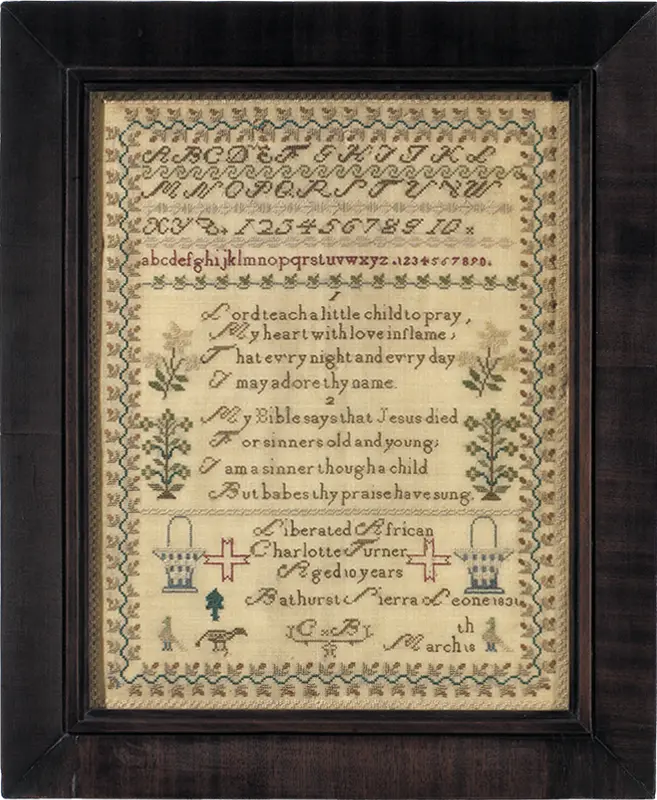

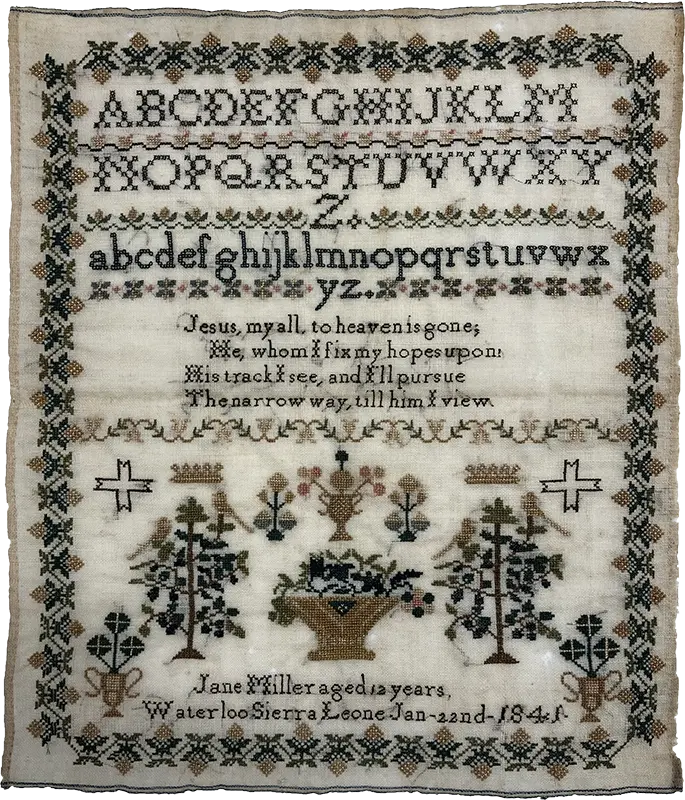

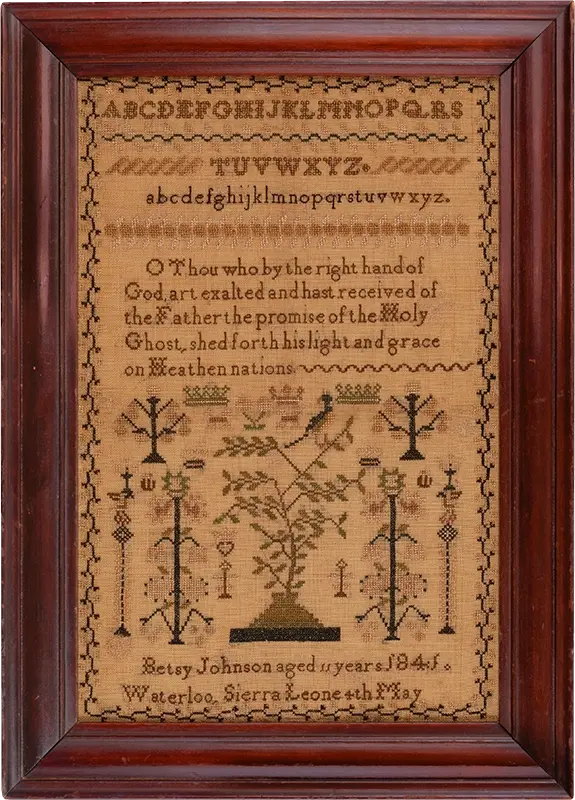

[Figure 1] Sampler by Betsy Johnson, Waterloo, 4 May, 1841. Silk on wool, 31.75 x 21cm, (photo credit: M. Finkel & Daughter)

Betsy Johnson’s sampler (figure 1) from 1841 may look like a usual schoolgirl sampler from mid-nineteenth century Great Britain or North America. But here is a surprise: it was produced by an African schoolgirl in West Africa under the instruction of a Eurafrican woman (and her African assistant) who had been taught needlework in Africa by an African American woman.

Thus, Betsy’s sampler is testimony not just to a schoolgirl’s proficiency in needlework but also to the diffuse and unexpected ways in which needlework skills were transferred to West Africa in the context of Christian missionary activities. It highlights the importance of Black women in this transfer and, more generally, their agency and experiences in the overlapping contexts of mission, the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade, and British colonialism on the African coast. This reminder of Black women’s contribution is particularly valuable because they rarely appear in contemporary mission documents and publications.

Betsy’s sampler is one of 26 known to exist today which were produced in Sierra Leone in the schools of the Church Missionary Society (CMS, an Anglican institution) between the 1820s and 1840s. They are preserved in the collections of various European and North American museums, archives, and private individuals. More such samplers may one day come to light.

These samplers can be identified by the designation ‘Sierra Leone’ or, if not, by the name of the village on the Sierra Leone Peninsula in which they were produced, such as Bathurst (figure 4), Gloucester, Kissy, Regent Town, Waterloo and (outside the colony) Port Lokko. They exhibit impressive needlework expertise, which was appreciated in the period and adds to their historical value. However, their main attraction stems from their uniqueness: no such sampler collection exists from any other mission field, although needlework was an intrinsic part of girls’ education in all mission fields in the nineteenth century, including the Gold Coast, South Africa and India.

The explanation for this uniqueness needs to be sought in the combination of various factors which can only be summarised here. (I have discussed these factors in detail in my article of 2010, see "About the Author".) Sierra Leone was an early British colony on the West African coast and, from 1804, a mission field of the Church Missionary Society. From 1808 the colony served as a destination for ‘recaptives’, that is, formerly enslaved Africans who were ‘rescued’ from the ‘illegal’ slave vessels which the British navy captured on the African coast in its attempt to suppress the transatlantic slave trade. Until 1863, an estimated 50,000 of these recaptives, then called ‘Liberated Africans’, settled in Sierra Leone in newly founded villages.

For the period from 1816 to 1824, the CMS cooperated with the colonial government in the administration of the recaptives; its missionaries acting as supervisors of the ‘recaptive’ villages and, from 1819, assuming responsibility for instructing the recaptive children. This cooperation opened a large and promising field for the CMS, but the mission was desperate for funds to employ more workers. The need for money persisted throughout the period, mainly because sickness and death constantly reduced the missionaries’ number.

CMS cooperation with the colonial government fell apart in the mid-1820s. The CMS gave up responsibility for the education of recaptive children and focused on colony-born children, that is those born in the colony to ‘recaptive’ parents. There was a brief reversal in 1829, when the CMS agreed to admit recaptive children to the schools it had meanwhile founded in several villages, but this lasted only a few years. From the early 1830s to 1850, CMS schools catered exclusively for colony-born children.

One scheme to motivate home support was the sponsorship programme, which ran from 1814 to 1819 and allowed sponsors in Britain to subsidise the education of a particular recaptive child. The fee was £5 annually for 6 years; in return the sponsor was allowed to name the child.

The production of samplers in the CMS schools and their dispatch to Britain seems to have grown out of this sponsorship programme. The sponsors (mainly British women and clergymen) were keen for information about the child for whose education they paid. Samplers were a means of giving it, showing the attainments and the potential of the girl who had stitched it. They were perfect propaganda items, lightweight, (seemingly) personal, giving the girl’s name and age, and, if she was a recaptive, identifying her as a ‘Liberated African’ – thus indicating that this was a child who had been rescued from the horrors of the slave ship. They were made to excite an emotional response.

Part of our response to the samplers – then as now – is the urge to find out more about the children who produced them. But this is usually impossible, due to lack of documentation. For this period, no village school records survive which identify the pupils. Information about the schools is given in the missionary correspondence (letters, reports and minutes of meetings). However, these records contain little detail about children, and even less about female children: the documents were normally produced by male missionaries, while it was their wives or other female employees of the mission who instructed the girls.

[Figure 2] View of Freetown from King Tom's point, across the bay (Missionary Register 1830, p. 287)

Unlike the girls who stitched the samplers, the needlework teachers under whose instruction the samplers were produced can often be identified, by combining the information given by the samplers (date and location), on the one hand, and, on the other, complementary data in the missionary sources. Moreover, the samplers betray the needlework instructresses by their distinct styles.

Betsy Johnson’s sampler (recently brought to my attention by Amy Finkel) is one of six samplers produced under the instruction of Jane Hickson, who worked as teacher for the CMS in Sierra Leone from 1826 until her death in March 1841.

In contrast to many of her female colleagues teaching needlework, Jane was not one of the European wives who had accompanied their missionary husband to Sierra Leone. She was born on the West African coast just north of Sierra Leone, of an English father and an African mother. Her father, Charles Hickson, was a slave trader; her mother may have been a local chief’s daughter, or herself one of the Eurafricans resulting from such unions which were common on this part of the coast.

From the age of about 5, Jane was educated in a CMS school in the Rio Pongo area (just north of Sierra Leone, in today’s Republic of Guinea), together with her older sister, Mary, and other local slave traders’ children. The instruction in needlework was an important part of her training by the missionary’s wife, an Afro-American woman who had come to Sierra Leone as a child, accompanying her parents as part of the ‘Nova Scotian’ immigration to Sierra Leone in 1792. The ‘Nova Scotians’ were Black loyalists who had fought on the British side during the American War of Independence and after the British defeat had settled in Nova Scotia.

Jane and Mary remained in the school for some fifteen years, interrupted only by an interval following their father’s conviction, in Sierra Leone in 1814, for engaging in the slave trade (which had been become illegal for British subjects in 1808). He was sentenced to three years’ hard labour in the colony and his children were ordered to move south to the colony. In the following year, Hickson was pardoned and returned to the coast north of the colony with the sixty enslaved persons whom he (‘legally’) owned. He died in 1818.

Around this time, Jane and Mary re-joined the missionary school which relocated from the Rio Pongo to the colony, first to the village of Leopold, then Kent and, finally, Gloucester. In May 1826, following the death of their Nova Scotian teacher, the school was moved to Kissy and placed in the charge of Mary, who had recently married a European CMS missionary. Jane, by then about 20 years old, worked there as teacher, paid by the colonial government.

In early 1829, Jane married a young CMS schoolmaster from Essex (in England), Edmund Boston, who had arrived in Sierra Leone the previous year. They were briefly stationed at Gloucester and then, from July 1829, at Kissy. They managed the schools in these places, Edmund officially in charge and Jane ‘assisting’, i.e., teaching, in the girls’ school. However, it needs little imagination to realise that Jane must have been an equal if not the senior partner in this relationship: she had the experience and was familiar with the people and their way of life, while for Edmund everything was new and probably rather startling.

In his report from Gloucester of June 1829, Edmund noted: ‘Mrs Boston instructs 21 of the elder girls in needlework, in which they have made some proficiency.’

[Figure 3] Sampler by Charlotte Turner, Bathurst, 18 March 1831. Silk on wool, 32.4 x 24.4 cm (Seattle Art Museum #2014.24.3, photo credit M. Finkel & Daughter)

Edmund died at Kissy on 8 June 1830, leaving Jane widowed after only 17 months of marriage – not an unusual experience in missionary circles in Sierra Leone, made famous as the ‘White Man’s Grave’ in the title of W. Harrison Rankin’s book of 1836. She had a daughter by Edmund, born perhaps after his death.

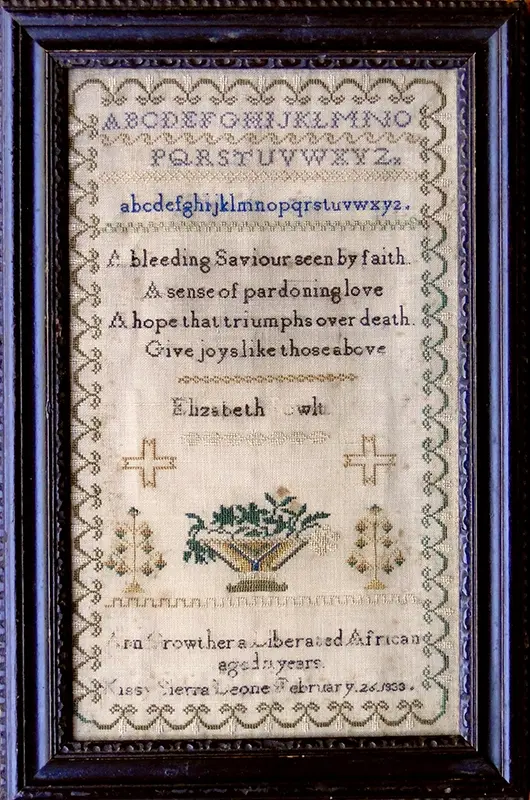

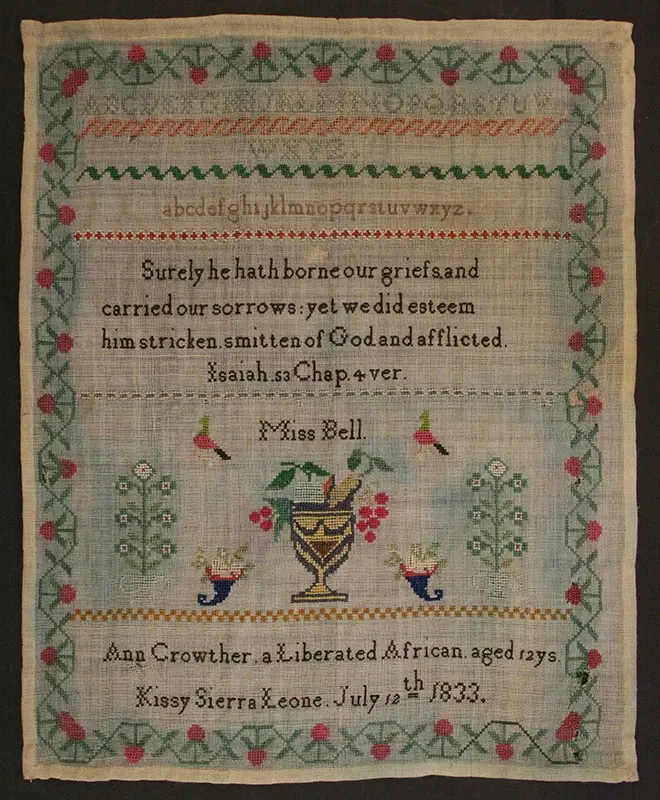

Following Edmund’s death, Jane remained at Kissy. She worked in the school until April 1835, with only a brief interruption in the first quarter of 1831, when she was posted to the village of Bathurst. For over year, she was in charge of the Kissy school, running it with the assistance of a series of recaptive teachers. By the end of the 1830, the number of pupils had reached 156 (with an average attendance of 129), including 67 girls. Of the latter, 24 were taught needlework by Jane, who, according to the missionary supervising Kissy mission station, expressed ‘her especial satisfaction with the progress which 8 of them are making.’

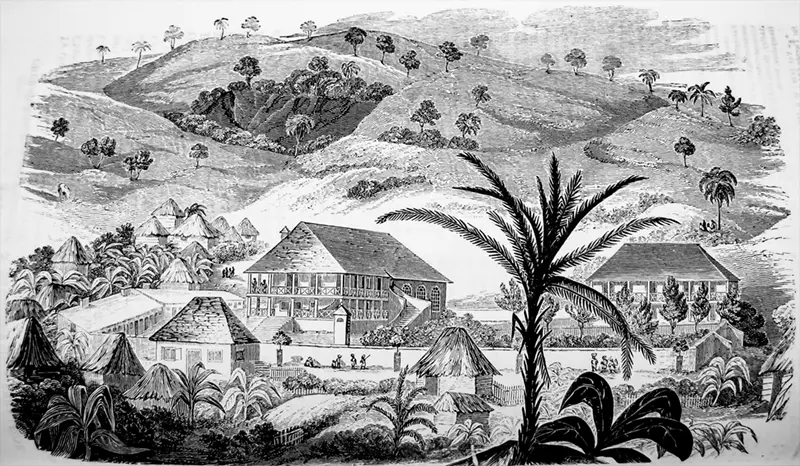

The early 1830s were a difficult period for the CMS in Sierra Leone, due to the fraught relationship with the colonial government and the lack of missionaries. Jane was a bedrock for the mission, competent and reliable, as was acknowledged in the reports by the male missionaries. Her value to the mission is also implied by her posting to the Bathurst school in the first quarter of 1831, where she stepped into the breach following the sudden exit of the missionary couple there. It was a large school with 250 children, including 147 recaptive girls. Jane and a female colleague taught the girls, reporting that ‘their progress in Needle-work is good.'

One sampler from this period survives, by Charlotte Turner (figure 3), ‘Liberated African’, dated 18th March 1831 and now held by the Seattle Art Museum.

The sampler’s style shows Jane’s influence rather than her colleague’s. The design, the borders, and the motifs are like those of the other samplers surviving from her classes, while those subsequently produced under her colleague’s instructions are simpler in design. It is perhaps no coincidence that the first surviving sampler made under Jane's instruction comes from the Bathurst school, which in the second half of the 1820s had been something of a sampler factory.

In April 1831, Jane returned to work in the Kissy school. In his report for the second quarter, the missionary supervising Kissy station acknowledged that due to her ‘constant attendance’ and the assistance of a recaptive male teacher, the school had progressed regularly and considerably.

[Figure 4] View of Bathurst village with the CMS mission house and church (Missionary Register 1829, p. 429)

From October 1831, a CMS schoolmaster, William Young from Newcastle (England), was posted to Kissy school and took charge of it. From then on, we have more detail about Jane’s work in the school as he regularly notes her activities in his reports. His transparent respect for her professionalism was accompanied by a growing (if hidden) admiration for her person. In late 1833, they married. In a letter to the CMS secretary in London announcing their marriage, William wrote that it had been ‘a subject of fervent prayer for nigh twelve months.’ Jane’s own thoughts and feelings are not recorded. Their first child, a boy, was born in August 1834.

Jane continued to instruct the girls in the scriptures, reading, writing and needlework. Her needlework classes were held from noon to 2 pm, sometimes assisted by another teacher. In September 1832, from thirty to forty girls attended the classes; by September 1833 the number had increased to 83. In March 1835, when the number was ‘about 70’, William reported that ‘progress in that branch of useful knowledge [i.e., needlework] is very satisfactory.’ Sampler-making for supporters of the mission was part of the needlework instruction: ‘Specimens of their work are in the possession of several very respectable supporters of our Society in England.’

Three samplers from this period are known. Two of them, dated February and July 1833, were produced by one girl, Ann Crowther (figure 5), a ‘Liberated African’ (one now held privately and the other by the CMS Archives at the Cadbury Research Library of the University of Birmingham, UK, reference number: Z95. Figure 6).

[Figure 5 ] Sampler by Ann Crowther, Kissy, 26 February 1833. Silk on wool, c.31 x c.18 cm (Private Collection, photo reproduced with permission by the owner)

[Figure 6] Sampler by Ann Crowther, Kissy, 12 July 1833. Silk on wool, 34.1 x 28 cm (© Church Mission Society. Reproduced with permission by the CMS Archives and the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham)

The third sampler was stitched by Jinny Driged and is dated June 1834. Its current whereabouts are not known, but there is a photograph in the CMS collections in Birmingham.

In April 1835 Jane and William were posted to Bathurst while the missionary couple stationed there went on furlough to England. Jane took charge of the needlework classes, assisted by the ‘Wife of our Native Assistant’, i.e., a recaptive teacher. 100 girls attended the classes in September. William contrasted their diligence in needlework with lack of ‘equal diligence to acquire a saving knowledge of their Saviour’, implying that the acquisition of practical skills mattered more to the girls than piety. In 1836 Jane and William went on furlough to England, with their two children.

Returning to Sierra Leone at the end of the year, they left their children behind at school, as was usual for missionaries at the time. Their son was just over 2 years old, whilst Jane’s daughter by Edmund, Mary, was about 5 years old. They would not see their son again: he died at school four years later.

Following their return to Sierra Leone in late 1836, they were stationed in Freetown for a year, where they established a school in the Gibraltar Town district of the town. At the beginning of 1838, they were posted to Waterloo, a ‘recaptive’ village in the south-east of the colony, twenty-one miles from Freetown (figure 2). They founded a school for colony-born children, their parents paying the school fees. In September 1838, William reported that 70 girls were being instructed in sewing by Jane, for two hours daily. However, she found the sewing class an uphill struggle as the girls were ‘exceedingly backward’.

After fifteen months in Waterloo, the couple were sent to work at Bathurst school again, for ten months. By then, they had another child and Jane was pregnant again. They returned to Waterloo in January 1840. In May, William reported that Jane had ‘a large number’ of girls in her needlework class and that they were making good progress. ‘They take delight chiefly in marking samplers.’

Two of these samplers survive. One, by Jane Miller (figure 7) from 22nd January 1841, is held by the CMS Archives at the Cadbury Research Library of the University of Birmingham, UK (reference number: MS874).

The other is Betsy Johnson’s sampler (figure 1). It was finished in May 1841 – two months after Jane’s death. However, the style is recognisably Jane’s. It seems likely that the sampler was started under her instruction, that she marked out the design, and that it was finished under the supervision of a ‘recaptive’ teacher, who is mentioned in William’s reports.

[Figure 7] Sampler by Jane Miller, Kissy, 22 January 1841. Silk on wool, 32.5 x 27.5 cm (© Church Mission Society. Reproduced with permission by the CMS and the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham)

Jane died in March 1841 of an (unidentified) illness. She was about 35 years old. Her death left William distraught at ‘the immeasurable loss’ which he had suffered: ‘Thus I am bereaved of the dearest earthly object I was permitted to enjoy. In her I have lost the beloved partner of my trials and cares, who helped me to bear the heat and burden of the day in this parched land of sickness and death.’ He also noted the setback which Jane’s death meant for the Church Missionary Society, as she had been ‘a faithful, persevering, and humble labourer’, although ‘[y]ou seldom witnessed her name in the Missionary Journals’.

This public invisibility was inherent in the position of women, and particularly Black women, working for the mission in the first half of the nineteenth century. Defined by their relation to a male missionary, hidden by changing their surname upon marriage, and prevented from directly corresponding with the mission headquarters in London, they left few traces in the records despite doing fundamental work for the mission.

However, the samplers themselves constitute traces which Jane Hickson/Boston/Young left to posterity. They are tokens of something even more valuable, albeit less quantifiable: the needlework skills which she taught African girls for fifteen years, giving them the potential for economic independence and thus laying the foundations for the emergence in Sierra Leone of the profession of seamstress.

Article published with permission of the author, © 2025 Silke Strickrodt

About the Author: Silke Strickrodt, PhD is a historian of West Africa with particular interest in Afro-European encounters in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. Her research interests include Christian missions, the Atlantic slave trade, education, family, marriage and gender.

She is the author of the article, ‘African girls’ samplers from mission schools in Sierra Leone (1820s to 1840s)’, History in Africa 37 (2010), 189-245 and is currently working on a book about mission samplers from Sierra Leone.

(For more detail, see www.silke-strickrodt.de)

Further information and a full bibliography will be provided in her future publications on this topic. She is keen to find more specimens.

![[Figure 2] View of Freetown from King Tom's point, across the bay (Missionary Register 1830, p. 287)](/sites/default/files/styles/wide/public/2025-03/Freetown_from_King_Tom%27s_Point_MR_web.webp?itok=1K3avgDc)