Girls in Delaware, the second-smallest state in the nation, produced about three hundred known samplers in a variety of styles between the 1740s and mid-1800s. New Castle County, the northernmost and most populated of Delaware's three counties, saw more sampler activity than the other two counties combined, with nearly two hundred known samplers. Girls who lived in Kent County in central Delaware produced nearly seventy samplers, or about one-third the number of samplers as New Castle. Rural Sussex County in the southern part of the state saw the fewest number of samplers; its girls stitched slightly fewer than forty samplers, or about one-fifth the number made in New Castle County.

Delaware Discoveries: Schoolgirl Samplers, 1750-1850, by Gloria Seaman Allen and Cynthia Shank Steinhoff, will be published later this year. The book, which is fully illustrated with photographs, documents Delaware samplers and their makers in the same manner as Dr. Allen's two earlier books did for samplers made in Maryland and the District of Columbia.

Samplers in New Castle County

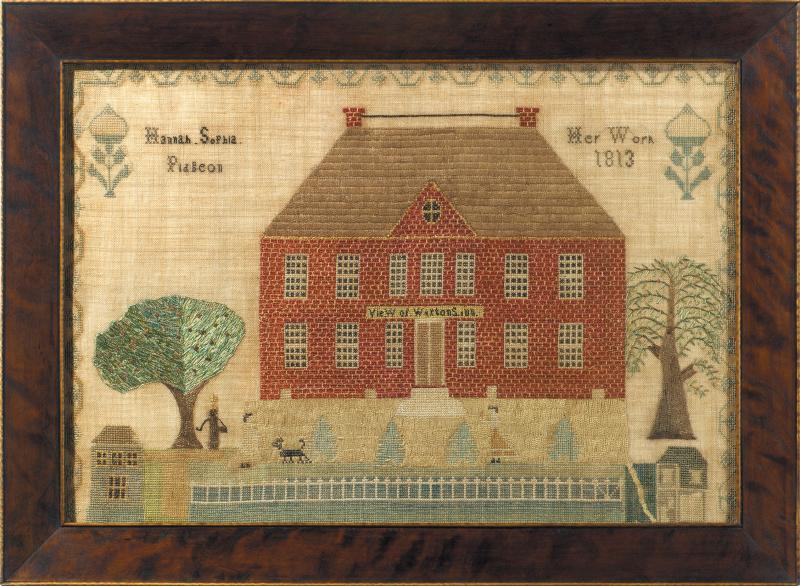

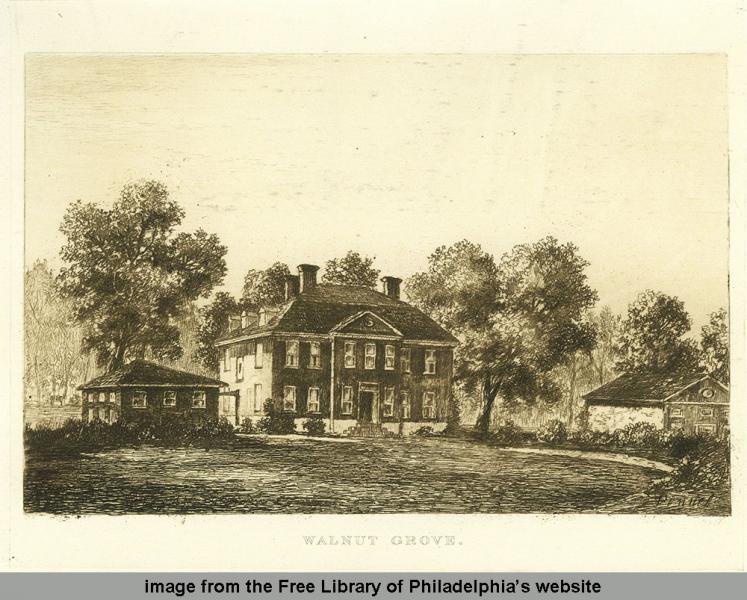

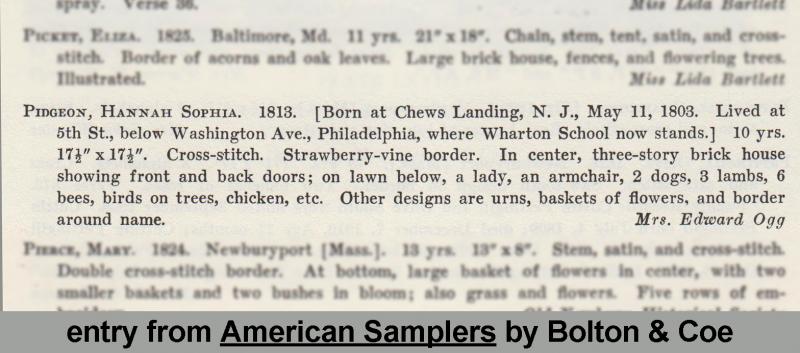

Wilmington, the largest city in the state, is located in New Castle County and Philadelphia is just over thirty miles to the northeast. Girls in New Castle County had easier access to schools and materials needed for samplers than those in the two more rural counties. New Castle girls many different styles of samplers, including many complex designs. They stitched samplers instructed or influenced by Quaker teachers. A style of samplers featuring compartments for verses or initials, ornate floral designs in baskets, and intricate floral borders persisted in New Castle County from the late 1700s through the 1830s. Some made alphabet samplers or variations on them.

Quaker Influences

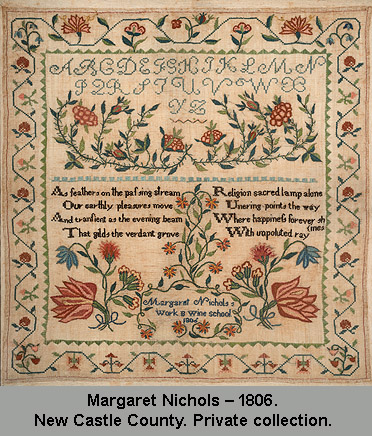

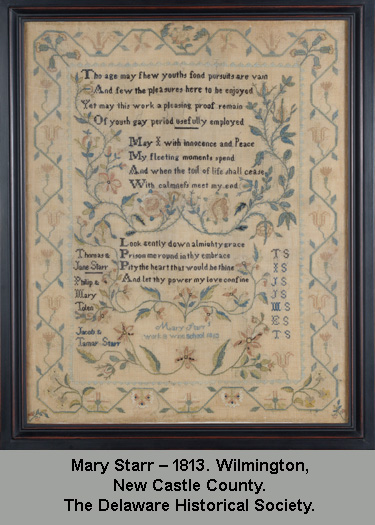

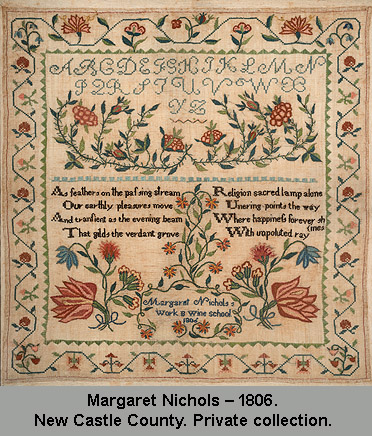

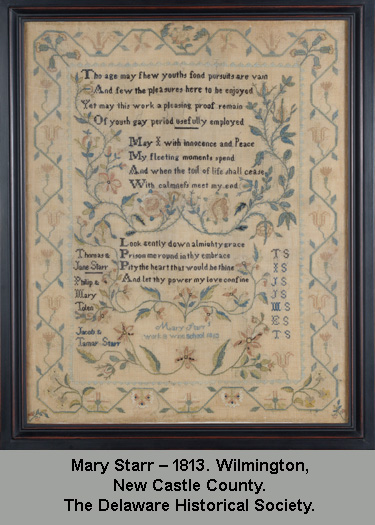

Margaret Nichols and Mary Starr both studied needlework with the well-known Quaker teacher, Susanna Pusey Harvey, whose students abbreviate her Brandywine School name as "B'Wine School" on samplers. The two girls had some similar elements on their samplers.

Margaret Nichol's sampler made in 1806 featured a floral border, alphabet at the top, and large floral motifs throughout the work. Two verses appear in the center and Margaret encased her name, school, and the date made in a wreath of flowers and stems. Margaret was the third daughter of four born in 1793 to Samuel Nichols and his wife, Ruth Mendenhall Nichols, who lived in Wilmington. She never married and after her parents' death, she resided with her nephew, Samuel Nichols Pusey, who operated a cotton manufacturing company at Front and Tatnall Streets in Wilmington. Margaret died in 1865 at age seventy-two and is buried with her parents and two sisters at the Wilmington Meeting burial ground.

Mary Starr completed her sampler in 1813, also under the direction of Susanna Pusey Harvey, and was likely one of Susanna's last students. It was in 1813 that Susanna married Samuel Malin and ended a teaching career that began before 1800 in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Three verses feature prominently on Mary's sampler, as do the names of her parents and grandparents and initials of her siblings. Mary was a daughter of Jacob Starr, a sea captain, and Tamar Tolen Starr of Wilmington. Little is know about Mary's later life.

Baskets

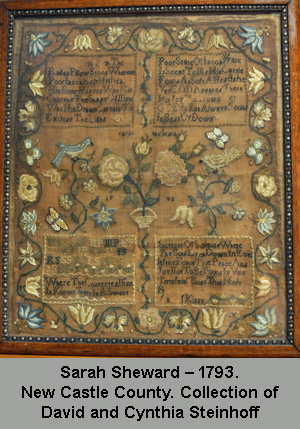

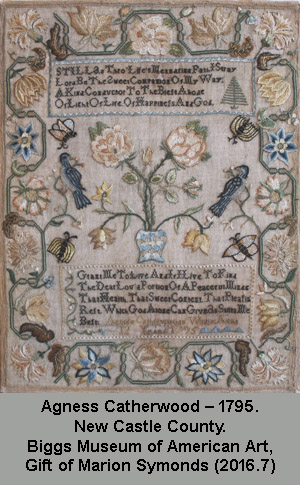

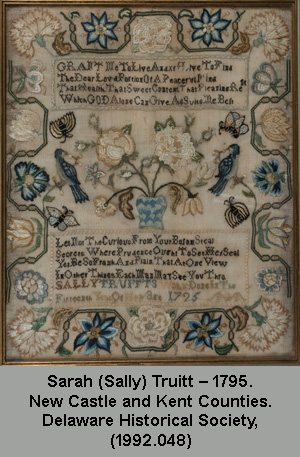

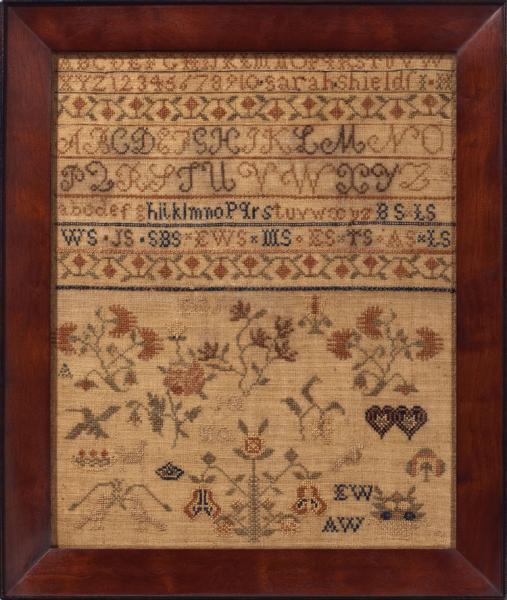

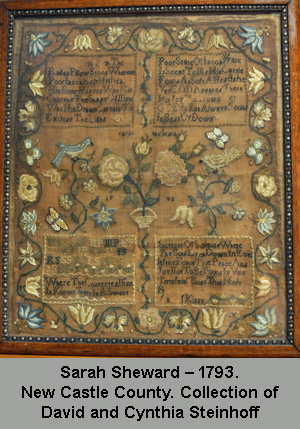

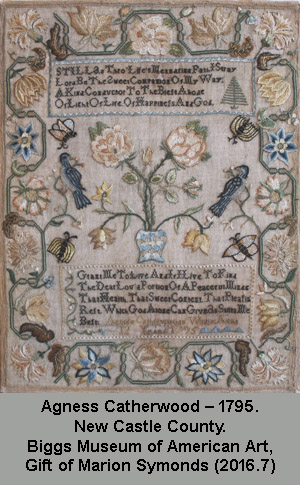

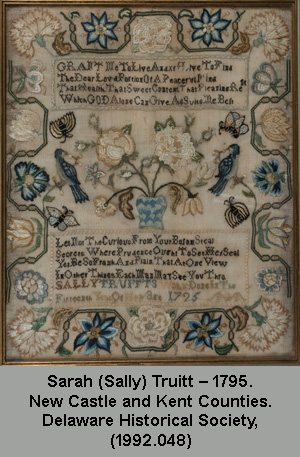

Three samplers represent the New Castle basket group. They are part of a group of six known samplers with very similar characteristics made between 1789 and 1795, probably in the Wilmington area, as well as an 1817 sampler with many of the same features, but a different border. While no teacher or school is mentioned on any of the samplers, it is likely that such complex samplers were made under the direction of an instructor. The common features of this group are ornate and colorful floral borders, a central basket containing more flowers, birds and butterflies, and compartments for text that can include verses, the stitcher's name, and family initials. Sarah Sheward, Agness Catherwood, and Sally Truitt stitched the three samplers representing this group.

Sarah Sheward's sampler, stitched in 1793, was discovered too late to appear in Delaware Discoveries. The central basket is small and contains a bouquet of two large flowers and several smaller buds. Sarah's name appears above the flowers with the date made below them. More flowers, two birds, and two butterflies appear on either side of the floral arrangement. She included four nearly square boxes that contain verses and family initials.

Sarah Sheward (1780-1850) was a daughter of James Sheward, a British naval physician, and Rest Perry, a Quaker from Wilmington. Sarah married George Whitelock, a Wilmington cabinetmaker, in 1805 and they had eight children. George died in 1833 after he and Sarah relocated to Baltimore, Maryland. Sarah died November 23, 1850. She still lived in Baltimore at the time of the 1850 census.

Agness Catherwood (1783-1802) stitched her 1795 sampler with two rectangular compartments holding verses. Her basket is slightly larger than Sarah Sheward's and she stitched two birds and four butterflies within the flowers. Agness opted to place her name and date made within the lower rectangle, and her border included more elaborate flowers and leaves than Sarah's.

Agness was a daughter of Andrew and Mary Catherwood, residents of Wilmington. Andrew and Agness died on the same day, October 1, 1802, likely from yellow fever. The outbreak that year began in Philadelphia and spread through Wilmington in September and October.

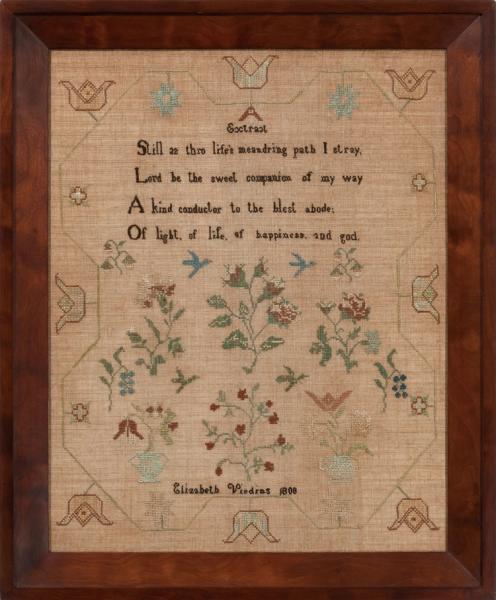

Sarah (Sally) Truitt also stitched her sampler in 1795. She and Agness Catherwood used the same verse, "Still as Thro' Life's Meandering Path I Stray…," which came from a collection of readings used in schools. Her multi-colored basket is much like Agness' and both girls included four butterflies and a pair of birds with their flowers. Sally also placed her name and the year the sampler was made inside the lower compartment.

Sally Truitt (1780-1803) was the only child of George Truitt and Margaret Hodgson Truitt. She grew up on the family farm near Felton in Kent County, Delaware, and may have boarded in Wilmington when she made her sampler. Her father served in the Delaware General Assembly for eighteen years and was Governor of Delaware from 1807 through 1811. Sally married Dr. James H. Fisher on March 19, 1801. She died July 15, 1803, nine days after their second son, Frederick, was born; the child also died.

Samplers from other areas of New Castle County

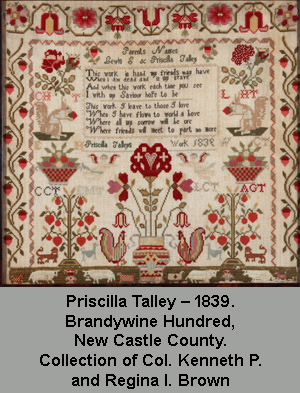

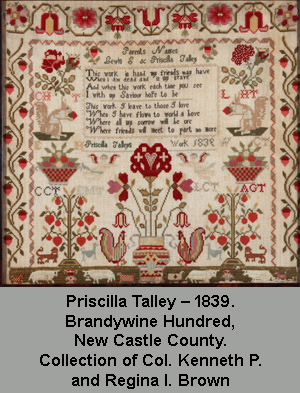

Priscilla Talley (1824-1899) stitched a sampler with family names and initials 1839 that resembled two others made about the same time. She used the color red extensively in her work and stitched floral borders at the top of her sampler, but placed strawberry vines at the sides. Instead of a border at the bottom, she created a barnyard of cows, sheep, dogs, lions, and two chickens in fanciful colors. One of the sheep sports a beige and rust checkered coat and the chickens are striped with many colors. Squirrels on either side of a box holding text complete the menagerie. Priscilla stitched her name and date under the box. Her sampler is so eye-catching that the authors selected it as the cover image for Delaware Discoveries.

The names of Priscilla's parents, the Reverend Lewis S. Talley and Priscilla Clark Talley, are stitched near the top of her samplers. The initials scattered through her work represent the names of her siblings. Only one set remains unidentified. "EH," placed to the left of Priscilla's name, could be her teacher. Priscilla's father was a Methodist minister and the family resided at Talley's Corner in Brandywine Hundred, New Castle County. About 1844, Priscilla married William C. McCracken, a farmer from near Aston, Delaware County, Pennsylvania. They had four daughters and one son.

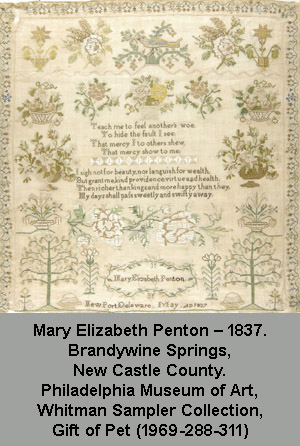

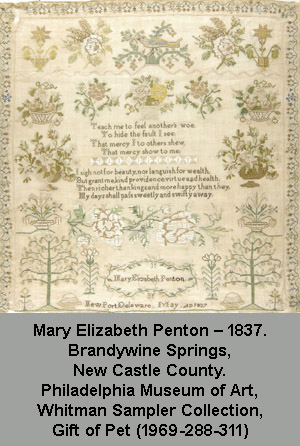

Mary Elizabeth Penton stitched her sampler in 1839 when her family lived in Brandywine Springs, New Castle County. She included many floral motifs and stitched two verses often found on samplers, "Teach Me to Feel Another's Woes…" and "I sigh not for beauty…" Little is known about her life prior to her marriage in the mid-1840s to another Brandywine Springs resident, Nathan Hiram Yearsley, the son of a blacksmith. The family remained in Delaware until about 1852, then moved to Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, before settling in Marshall Township, Taylor County, Iowa, by 1885, where Nathan and Thomas, the couple's oldest son, farmed. Nathan died in 1890 and Mary Elizabeth and son Thomas remained in Iowa for another fifteen years. In 1906 Mary Elizabeth, Thomas, and Thomas' niece and nephew relocated to the province of Alberta, Canada, where they obtained a homestead under the Dominion Lands Act. Thomas improved the property and farmed. Mary Elizabeth Penton Yearsley died in 1911 and Thomas followed the next year. They are both buried in Highwood Cemetery in High River, Alberta, Canada.

Mary Elizabeth Penton stitched her sampler in 1839 when her family lived in Brandywine Springs, New Castle County. She included many floral motifs and stitched two verses often found on samplers, "Teach Me to Feel Another's Woes…" and "I sigh not for beauty…" Little is known about her life prior to her marriage in the mid-1840s to another Brandywine Springs resident, Nathan Hiram Yearsley, the son of a blacksmith. The family remained in Delaware until about 1852, then moved to Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, before settling in Marshall Township, Taylor County, Iowa, by 1885, where Nathan and Thomas, the couple's oldest son, farmed. Nathan died in 1890 and Mary Elizabeth and son Thomas remained in Iowa for another fifteen years. In 1906 Mary Elizabeth, Thomas, and Thomas' niece and nephew relocated to the province of Alberta, Canada, where they obtained a homestead under the Dominion Lands Act. Thomas improved the property and farmed. Mary Elizabeth Penton Yearsley died in 1911 and Thomas followed the next year. They are both buried in Highwood Cemetery in High River, Alberta, Canada.

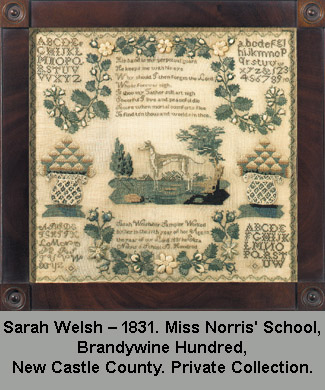

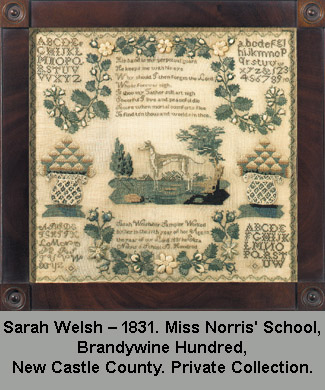

Sarah Welsh (ca. 1820-?) is one of two known samplers from Miss Eliza Norris' school in "B Hundred" (Brandywine Hundred). She included Miss Norris' name and the abbreviated version of the school's location at the bottom on her sampler, along with the date 1831. Sarah stitched an alphabet in the four corners of the sampler, using a different font for each one. A floral vine occupies space at the bottom of the sampler, encasing Sarah's attribution, and another at the top provides a cover for eight lines from two different hymns. She stitched a large dog at the center of the sampler with a floral basket at each side.

Sarah Welsh (ca. 1820-?) is one of two known samplers from Miss Eliza Norris' school in "B Hundred" (Brandywine Hundred). She included Miss Norris' name and the abbreviated version of the school's location at the bottom on her sampler, along with the date 1831. Sarah stitched an alphabet in the four corners of the sampler, using a different font for each one. A floral vine occupies space at the bottom of the sampler, encasing Sarah's attribution, and another at the top provides a cover for eight lines from two different hymns. She stitched a large dog at the center of the sampler with a floral basket at each side.

Miss Eliza Norris may be the same teacher who worked at the Brandywine Manufacturers Sunday School (BMSS), operated by the du Pont family for young employees of its workforce at the Hagley Powder Mills. Unlike today's Sunday schools, Brandywine and other similar schools offered classes in basic education on Sunday, the only day of the week when employees did not work. A student by the name of Sarah Welsh attended BMSS at the time Eliza Norris taught there, as did a girl named Mary Orr, the name on the other known sampler from Miss Norris' school. Both girls are mentioned in the BMSS academic records. Another piece of evidence linking Sarah and Miss Norris to BMSS is the first quatrain at the top of her sampler, which is from a collection of hymns published by the American Sunday School Union, which supported schools such as BMSS.

Sarah Welsh was a daughter of Hugh Welsh and his wife, Ellen. A brother, John, who was born in 1818, attended BMSS at the same time as his sister. A note on Sarah's BMSS record states that she "Ceased attending July 1834. Married to ?". Sarah and her mother may be the Sarah Welch (sic), age 28, and Ellene Welch (sic), age 60, residing in Christiana Hundred, New Castle County, in the 1850 census.

Samplers in Kent County

Girls attending Southern Boarding School, a Quaker school located in Duck Creek in northern Kent County, produced more than twenty-five samplers over its short existence. Samplers were made in other areas of the county as well. While Kent County is home to Delaware's capital, Dover, it is much more rural than its northern neighbor, New Castle County. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Kent County had a predominantly agricultural economy and the landscape was dotted with farms and small towns and villages.

Samplers from Southern Boarding School

Samplers from Southern Boarding School

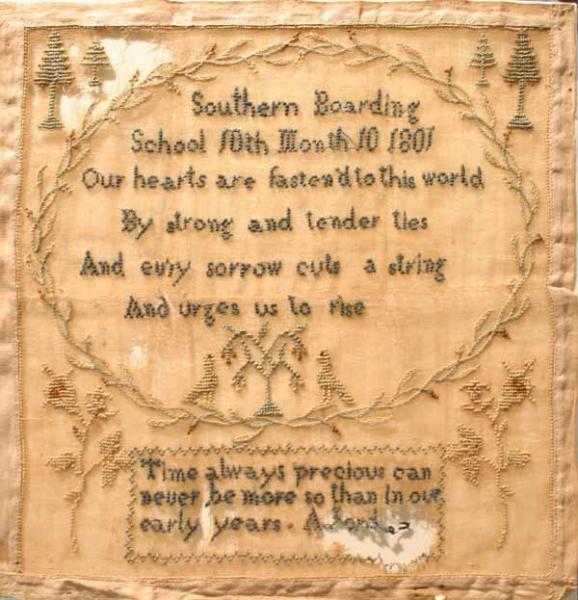

The Society of Friends, or Quakers, established Southern Boarding School in Duck Creek (now Smyrna) so that Quaker children living in southern Delaware and the Eastern Shore counties of Maryland could get an education tied to their religion. The coeducational school operated in two buildings on Methodist Street, now Mount Vernon Street, from 1801 until about 1806. Some teachers and students relocated to a Quaker school in Camden, about fifteen miles south of Duck Creek, when Southern Boarding School closed.

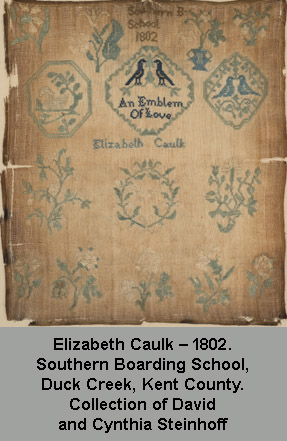

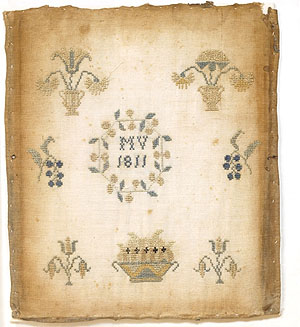

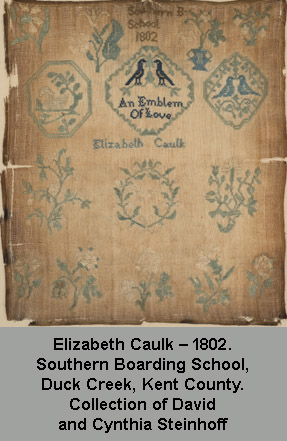

Girls at Southern Boarding School made several styles of samplers. Elizabeth Caulk stitched a Quaker motif sampler in 1802. She included three octagonal cartouches, one containing a swan, another paired birds, and the third, the "An Emblem of Love" motto. She included several floral motifs, all typical of those found on Quaker samplers, and a floral vine wreath in which she stitched the initials "EY," representing her teacher, Elizabeth Yarnall.

Isaac Caulk, Elizabeth's father, was originally from Kent County, Maryland, and he married Elizabeth Molleston at Three Runs Meeting near Milford, Kent County, Delaware. The Caulk family lived in Cecil County, Maryland, for the first few years after Elizabeth and Isaac married, then relocated to Kent County, Maryland. Elizabeth married Samuel Cox on December 19, 1821, and the couple lived in Harford County, Maryland, where Samuel's parents also resided. They were members of the Deer Creek Meeting in Harford County, which took disciplinary action against Samuel and Elizabeth Cox and their two sons, Isaac and Oliver in 1835. The action referred to matters of faith, and the Cox family was not mentioned again in the minutes of Deer Creek Meeting.

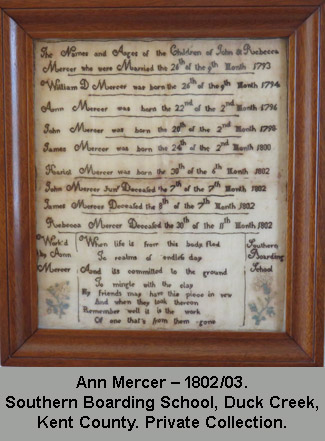

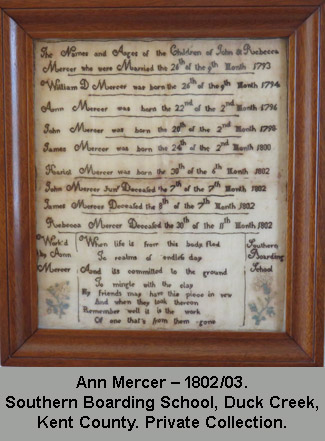

Ann Mercer (1796-1851) stitched a family record sampler at Southern Boarding School about 1803, including the name of the school on the sampler. She included a short verse at the bottom of her sampler, and at the top, details about her family. She stitched her parents' names and marriage date, followed by the names and birthdates of the five children in the family. She added the death dates of her brother James, her mother Rebecca, and John Mercer, either her brother or her father. Rebecca died just two months after the birth of her last child, Harriet, and a few weeks after the deaths of James and John. Ann later attended the Moravian school in Lititz, Pennsylvania, along with her sister, Harriet.

Ann married David Davis in Cecil County on December 19, 1811. David died on July 25, 1814; the younger of their two children, named after his father, was born eight months after his father's death. Ann then married Franklin Betts, a farmer from Massachusetts, and the family lived in Otsego County, New York, where Ann died on November 25, 1851. Ann Mercer's descendants include a circuit court judge from Illinois who later became a United States Supreme Court justice and two Presidents of the United States.

Samplers Elsewhere in Kent County

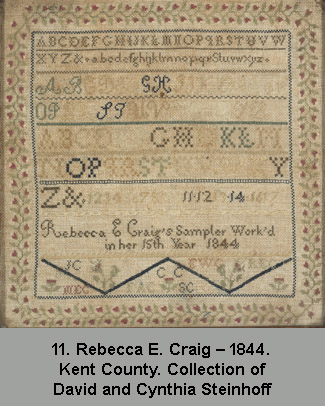

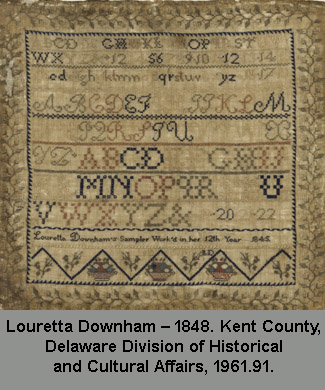

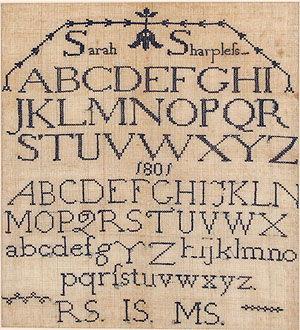

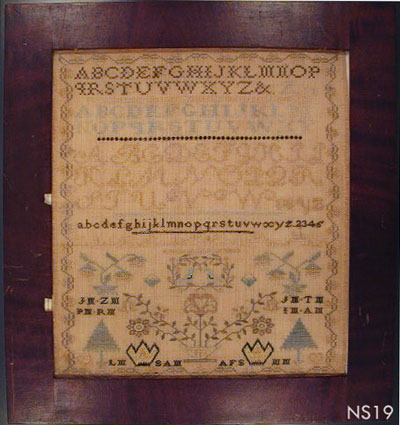

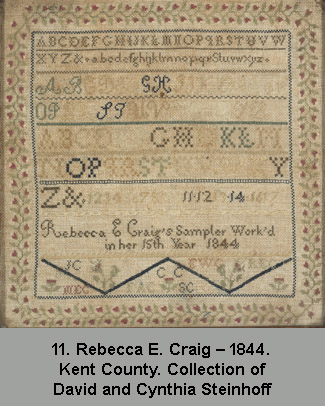

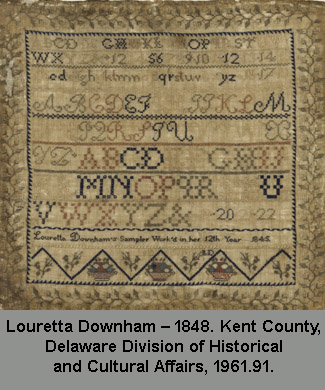

Two other samplers from Kent County closely resemble each other and may be evidence of a school or teacher offering needlework instruction in the area where the girls lived. Rebecca E. (Ellen) Craig and Louretta Downham worked their samplers in 1844 and 1845, respectively. The girls separated rows of letters, numerals, text, and motifs with narrow dividing bands. They stitched several alphabets at the top, ending the final alphabet with an ampersand, and worked numerals on their samplers, but in different locations. Beneath the alphabets and numerals, Rebecca stitched "Rebecca E. Craig's Sampler Work'd in her 15th Year 1844"; Louretta used the same language to report that she made her sampler in her 12th year in 1845. The bottom row in each sampler included a zigzag line with motifs and family initials stitched in the open areas. Initials on Rebecca's sampler represented her parents and siblings, and Louretta stitched her own initials and those of her parents. Rebecca's motifs were small, individual flowers, while Louretta included a few small flowers, along with three flower baskets that were more complex. Both girls included an outer floral vine border and a narrow inner border, which Rebecca worked in cross stitches and Louretta in sawtooth stitches.

Rebecca Craig was a daughter of John Craig and Rachel Wallace Craig, who married in 1814. The Craig family lived on a farm in Dover Hundred about seven miles southwest of the state capital, Dover. John died in 1832, shortly after the birth of the family's youngest child, also named John, in 1831. The family remained on the farm until Rebecca's death in 1869. In 1856, Rebecca married Elisha Wright, who farmed with his father in Dover Hundred near the village of Hartley. The Wrights had six sons and one daughter; four of their sons and their daughter died as infants or young children. Rebecca and Elisha remained on the farm until their deaths within less than two years of one another, Rebecca on April 21, 1903, and Elisha on December 14, 1904. Both are buried at Bryn Zion Cemetery in Kenton, Kent County, along with other family members.

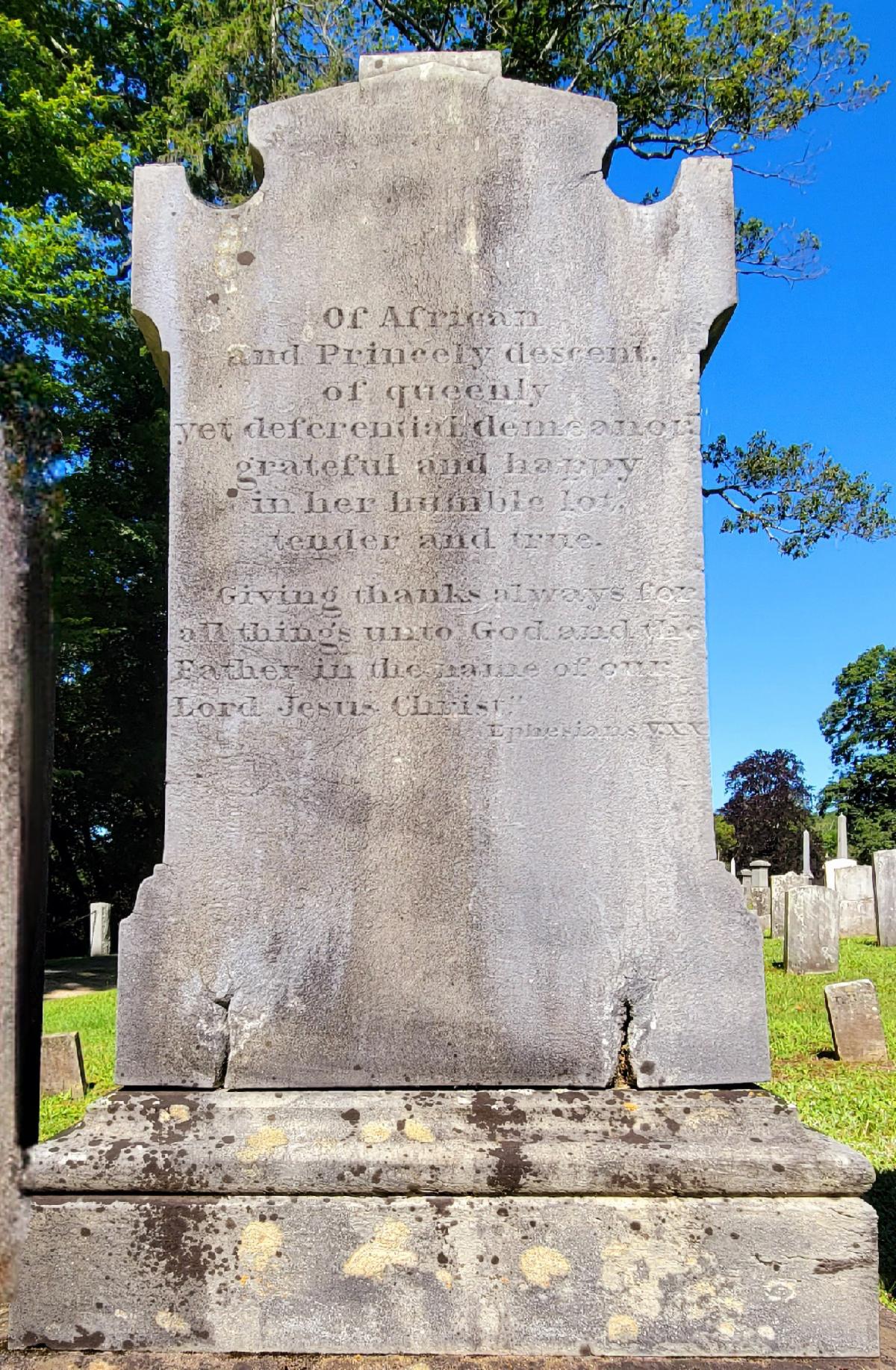

Louretta Downham (1833-1849) was born Louretta Fowler and came to the Downham family via an indenture. The Kent County Trustees of the Poor sent her to live with James Downham and his wife, Tamza (Tamsey) Downham in 1837 to learn "housewifery," when she was just four years old. They were required to provide a basic education for her, which seemed to have included needlework. Louretta died in 1849 at age fifteen, according to her tombstone, though other sources record her death as 1850. At the time of her death, she was living and working in the household of Samuel Broadway Cooper. She was buried in the Cooper Family Cemetery near the Kent County town of Petersburg, about five miles from the Craig farm. Louretta's tombstone is inscribed with her name, birth and death dates, and the notation that she was the "Adopted dau. of James Downham," though no confirmation of a legal adoption has been found.

Louretta Downham (1833-1849) was born Louretta Fowler and came to the Downham family via an indenture. The Kent County Trustees of the Poor sent her to live with James Downham and his wife, Tamza (Tamsey) Downham in 1837 to learn "housewifery," when she was just four years old. They were required to provide a basic education for her, which seemed to have included needlework. Louretta died in 1849 at age fifteen, according to her tombstone, though other sources record her death as 1850. At the time of her death, she was living and working in the household of Samuel Broadway Cooper. She was buried in the Cooper Family Cemetery near the Kent County town of Petersburg, about five miles from the Craig farm. Louretta's tombstone is inscribed with her name, birth and death dates, and the notation that she was the "Adopted dau. of James Downham," though no confirmation of a legal adoption has been found.

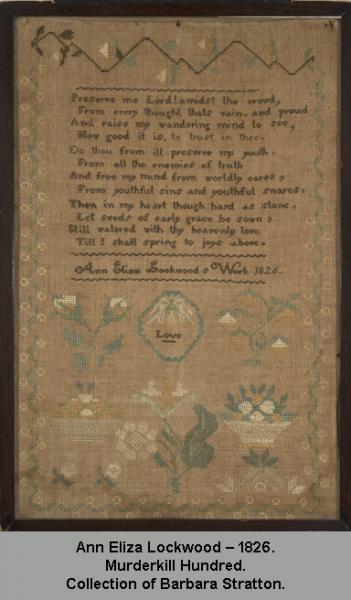

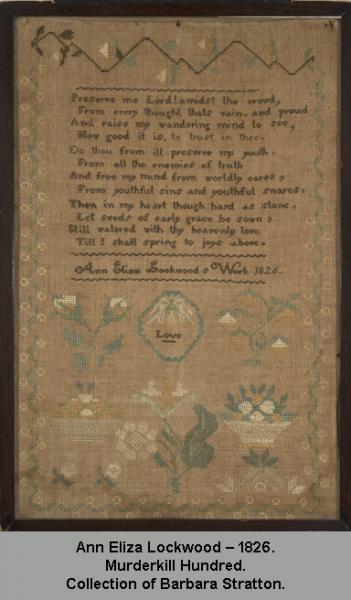

Ann Eliza Lockwood (1816-1896) stitched her sampler in 1826. It is a long vertical rectangle, of a size and shape frequently seen in the two lower Delaware Counties, though many of those samplers include only alphabets. At the top of her sampler under a zigzag border, Ann Eliza stitched a long verse, "The Youth's Request," that has appeared on other samplers. She stitched her name and the date made beneath the verse, followed by a group of Quaker motifs. She added a floral vine border along the sides and bottom of the sampler.

Ann Eliza was a daughter of William Kirkley Lockwood and his wife, Mary Polk Hayes Lockwood. She spent her early years in Murderkill and Saint Jones Hundreds in Kent County. Her mother died from complications of childbirth when Ann Eliza was just four years old. The Lockwoods maintained a close relationship with Mary Lockwood's parents after her death, and Mary's step-mother, Ann Bell Emerson Hayes, along with William Lockwood's half-sister, Martha Lockwood, stepped in to assist with raising the children. Ann Hayes, a member of the Society of Friends, may have been responsible for the Quaker motifs on Ann Eliza's sampler.

Anne Eliza came from a military and political family. Her brother, General Henry Hayes Lockwood, distinguished himself in the Union Army during the Civil War. Her father, William Kirkley Lockwood, served in the U.S. Navy for two years before settling in Murderkill Hundred, where he joined the Delaware Militia's Fifth Regiment and saw active duty during the War of 1812. He later commanded the Fifth Regiment, holding the title of colonel. After relocating to Dover, he served in a number of government roles, including register of wills, register of the Court of Chancery, clerk of the Orphans' Court, and Dover town commissioner, as well as representing Kent County in the Delaware House of Representatives.

Prior to 1844, Ann Eliza Lockwood married Henry M. Godwin, a member of a prominent Caroline County, Maryland, family. They had one son who lived for less than a year and four daughters. Henry represented Caroline County in the Maryland House of Delegates. He died in 1853 while in Annapolis, leaving Ann Eliza with three young children and pregnant with their fourth, who was born eight days after her father's death. After the loss of Henry, Ann Eliza and her children moved to her father's residence in Dover. Ann Eliza died in 1896 and is buried at Christ Episcopal Church Cemetery with her parents and children.

Samplers in Sussex County

Sussex County is the southernmost county in Delaware. It borders Maryland on the west and south, and the Delaware River and Bay and the Atlantic Ocean on the east. The town of Lewes at the mouth of the Delaware Bay was home to the first European settlement in the state in 1631. Coastal areas today are popular vacation and retirement destinations, while inland areas are rural with an economy based on agriculture. Travel in the area during the days when girls made samplers was complicated by the marshy soil, particularly near rivers, creeks, and bays. It was often easier to travel by boat than by land on horseback or in a carriage.

Lewes was the center of sampler making activity in Sussex County during the 1800s. The number of known samplers made in Lewes schools is approximately equal to those made elsewhere in the county. There are no known needlework teachers or schools that offered needlework instruction in other areas of Sussex County. Samplers made in Lewes schools have distinctive styles and those in other parts of the county tend toward alphabet or genealogical samplers, including family record samplers.

Samplers in Lewes

Mrs. Bowers and Mrs. Thompson operated two needlework schools in Lewes at different times. Known samplers from Mrs. George (Eliza) Bowers' school are dated between 1806 and 1808, though Mrs. Bowers' name is not stitched on them, and again between 1817 and 1823 when her name appears on most of the samplers. The earlier samplers attributed to Mrs. Bowers are nearly identical to one another and resemble some of the later samplers that do include her name; later samplers include different styles as well. Mrs. Thompson's school operated at least from 1831 through 1833.

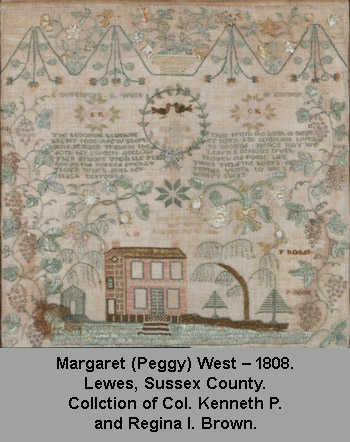

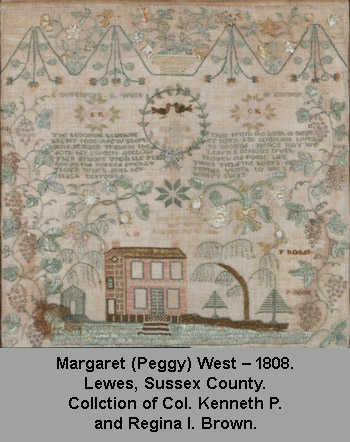

Margaret (Peggy) West (ca. 1799 – 1860) stitched her sampler in 1808. Her work and others in this group feature an abundance of vines and flowers, houses with lawns, and Quaker motifs. All include verses, though they differ from sampler to sampler. Peggy West was a daughter of Robert and Naomi Thompson West. She married Elisha Dickerson Cullen, an attorney in Georgetown, the seat of Sussex County, in 1822. They had six children, including a son who also became an attorney. Elisha served in the Delaware House of Representatives for one term. Peggy Cullen died in 1860 and her husband in 1862. They are buried at Lewes Presbyterian Church, along with Peggy's parents, several of their children, and some of Peggy's siblings.

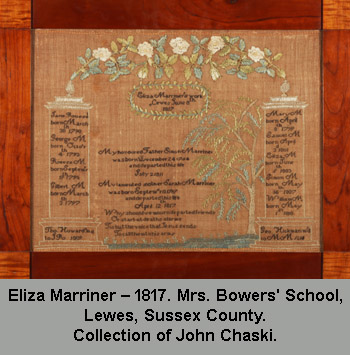

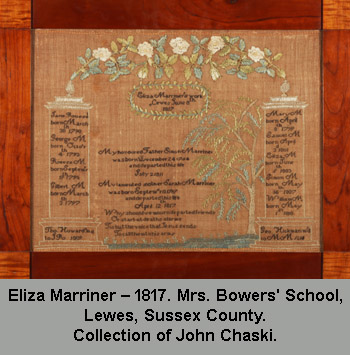

Eliza Marriner (1803-1881) made her sampler in 1817 and it is attributed to Mrs. Bowers' School. Her genealogical sampler provides detailed information about her family listed in two columns, their tops linked by a leafy vine. A tree stands next to the right column and more family details are stitched between it and the left column.

Eliza Marriner (1803-1881) made her sampler in 1817 and it is attributed to Mrs. Bowers' School. Her genealogical sampler provides detailed information about her family listed in two columns, their tops linked by a leafy vine. A tree stands next to the right column and more family details are stitched between it and the left column.

Eliza was one of ten children born to Simon and Sarah Wolfe Marriner, who resided in Lewes. As was the case with several Lewes sampler makers, Eliza had male relatives who were Delaware River and Bay pilots, the men who guided ships up and down the dangerous waters between the Atlantic Ocean and ports along the Delaware River up to Philadelphia. Her brother Gilbert was a pilot. His wife Deborah was a member of the Maull family; more than forty of her male relatives served as pilots between the early 1700s and early 1900s. Eliza's father operated a tavern in Lewes. After his death in 1811, her mother, Sarah, acquired his license and managed the tavern until her death in 1817. Research shows that tavern keeper was one of a few occupations open to women at the time and was considered to be an acceptable way for a woman to support herself and her children.

Eliza married John Henry Oberteuffer in 1828. They had three sons and two daughters and resided in Philadelphia, where John was an importer of silks. Eliza died in 1881 and John in 1871.

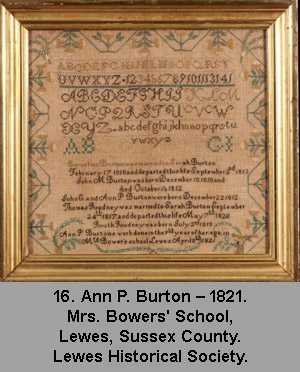

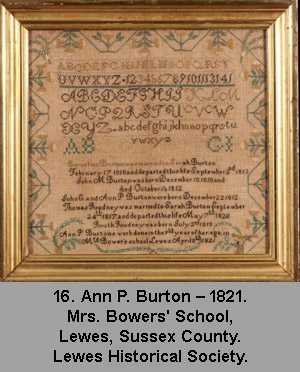

Ann P. Burton worked a sampler in 1821, noting that it was made at "Mrs. Bower's School Lewes." It is a style that is very similar to several others from the school. She also included such family details as the names and marriage date for her parents, Cornelius and Sarah Burton, and the births, with dates, of her siblings. She noted the death dates of her father and brother John M. Following her father's death, her mother married Thomas Rodney, and Ann reported their marriage and the birth of their daughter, Ruth.

Ann P. Burton worked a sampler in 1821, noting that it was made at "Mrs. Bower's School Lewes." It is a style that is very similar to several others from the school. She also included such family details as the names and marriage date for her parents, Cornelius and Sarah Burton, and the births, with dates, of her siblings. She noted the death dates of her father and brother John M. Following her father's death, her mother married Thomas Rodney, and Ann reported their marriage and the birth of their daughter, Ruth.

Because of the early death of Ann's father, the courts appointed a guardian to look after Cornelius' estate, especially for the benefit of his children. Sarah administered the estate and records show payments to Mrs. Bowers' school for Ann's education. She later attended another school in Lewes conducted by Dr. William Harris and one in Milton operated by the Reverend Shadrach Howell Terry, a Presbyterian minister.

Ann married Reverend Nathan Kingsbury, a minister at St. George's Chapel in Indian River Hundred, Sussex County, and St. Peter's Episcopal Church in Lewes. Her husband also kept a school for young ladies in Georgetown, the Sussex County seat. Ann died in 1837 and is buried in St. Peters Churchyard in Lewes.

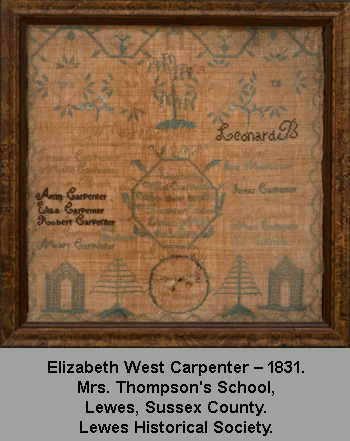

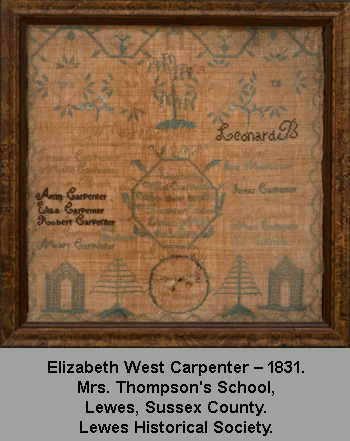

Elizabeth West Carpenter made her sampler under the direction of Mrs. Thopson in 1831. Her sampler includes a bounty of family information, though some is recorded with initials. She includes her parents' and sibling's information. Three of her siblings were married at the time Elizabeth stitched her sampler; she listed their spouses, and for one sister, the initials of her four children.

Elizabeth West Carpenter made her sampler under the direction of Mrs. Thopson in 1831. Her sampler includes a bounty of family information, though some is recorded with initials. She includes her parents' and sibling's information. Three of her siblings were married at the time Elizabeth stitched her sampler; she listed their spouses, and for one sister, the initials of her four children.

Elizabeth was one of twelve children born to James Carpenter and Mary Dean Carpenter, who married in Lewes in 1798. Prior to 1838, Elizabeth married Captain Henry Virden, a Delaware Bay, and River pilot. They had at least six children and three of their sons also became pilots. Their son John Penrose Virden was elected president of the Delaware Bay and River Pilots Association when it formed in 1896 and he served in this role for twenty-one years. Elizabeth died at age seventy-five and is buried in the churchyard at St. Peter's Episcopal Church in Lewes, along with her parents, husband, several siblings, and daughter, Annie.

Sampler from Sussex County

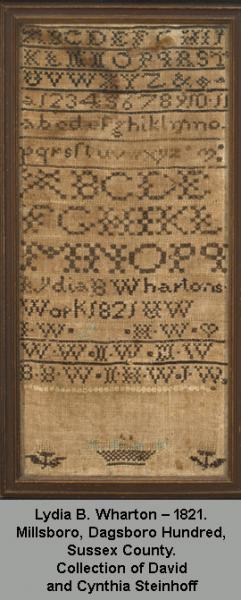

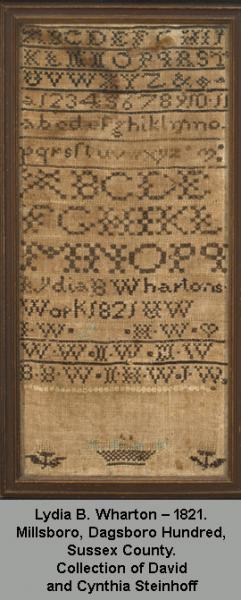

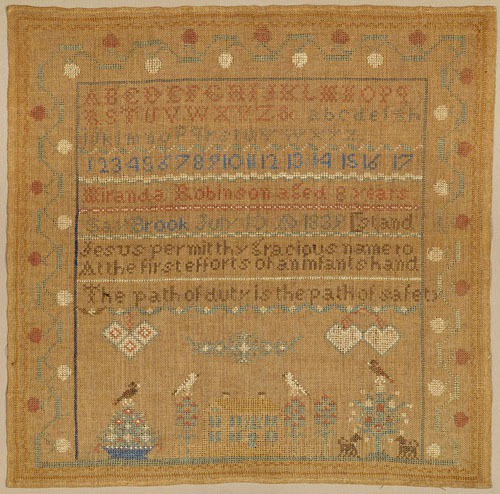

Lydia B. Wharton (1809-1876) made her sampler in 1821. It is a long rectangle, a common form shape for samplers in Sussex County. While at first glance, her sampler appears to be a simple alphabet sampler with a few small motifs, a closer examination revealed more complicated stitches that are not always seen on alphabet samplers. In addition to cross stitches over two threads, Lydia used double backstitch, queen stitch, cross stitch over one thread, Algerian eye stitch, and rice stitch. She included the initials of her parents and siblings.

Lydia was a daughter of Isaiah and Hetty Wharton, who lived in the Millsboro area of Dagsboro Hundred. Hetty was most like a member of the large Burton family found in Sussex County. The Whartons and Burtons settled in Delaware and neighboring Maryland counties in the 1600s. Isaiah owned and farmed land in Dagsboro Hundred along Indian River and its tributaries. He died in 1815, leaving several young children. Hetty married Thomas Robinson shortly after Isaiah's death and the court appointed him as the children's guardian. The records for Isaiah's estate show payments for the children's education.

In 1831, Lydia married Robert Bell Houston, whose family owned a farm near the Whartons. They had nine children, all boys. Robert inherited some of his family's land in the Millsboro area. He and his sons were active in their community and local and state politics. Robert was a delegate to the Fourth Constitutional Convention in Delaware and son John was state treasurer for four years. Another son, Henry Aydelotte, taught school, served in the U.S. House of Representatives for two years and was a member of the Sussex County school commission. He and a partner founded a company in 1890 that manufactured baskets for agricultural use, responding to a documented need created by growing farm production in the state. They adopted modern manufacturing techniques and their efficient company soon became the second largest producer of baskets in the state. A third son, Charles Bell, served as a director of a local bank and a trustee of the county almshouse and was elected to the state senate, serving as its speaker in 1893.

Lydia died in 1876 and Robert, in 1892. Their burial location is not known.

--------------------------------------

The Biggs Museum of American Art in Dover, Delaware, will hold an exhibit of about 125 Delaware samplers from May 19 through July 22, 2018. The Biggs will also host a one-day symposium about Delaware samplers on Saturday, June 9, 2018. Visit the Biggs website at http://www.biggsmuseum.orgor telephone 302-674-2111 for details.

Delaware Discoveries: Schoolgirl Samplers, 1750-1850, by Dr. Gloria Seaman Allen and Cynthia Shank Steinhoff is now available for sale at the Biggs Museum.*

*updated

How to ensure the survival of the sect? Look to the next generation. As J. William Frost stated in The Quaker Family in America, the only way to preserve Quakerism at this time “was for the children to adopt, preserve, and pass the faith on to their descendants. The children had to hold to the truth with the same degree of fervor as their parents.”

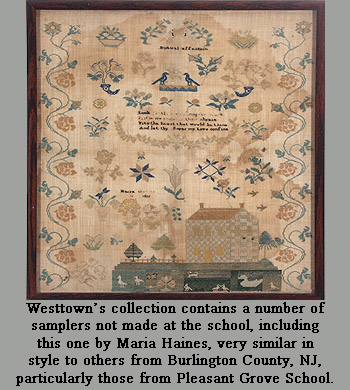

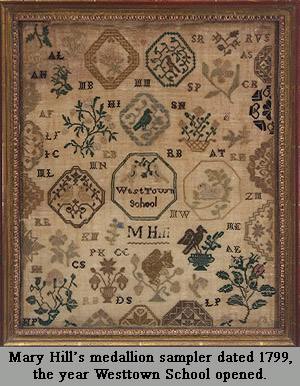

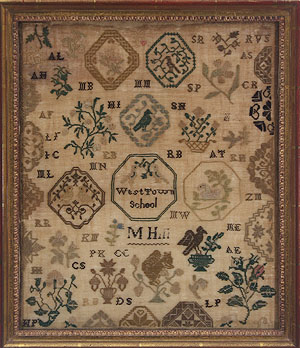

How to ensure the survival of the sect? Look to the next generation. As J. William Frost stated in The Quaker Family in America, the only way to preserve Quakerism at this time “was for the children to adopt, preserve, and pass the faith on to their descendants. The children had to hold to the truth with the same degree of fervor as their parents.” Some two hundred years after the opening of Westtown, there still is a plentiful body of needlework samplers made by Westtown girls that examined as a whole offers a window into the sewing school at Westtown. A look at over 260 samplers positively identified as made by students while at Westtown (about a third of which are in the school’s collection) suggests what may have transpired in that classroom so long ago. Was there a particular order in which the different types of samplers were made by a student? Was there a type of sampler made most often? Did styles change over the decades that sewing was part of the curriculum? And that ever vexing question: Does the use of variant spellings of the school name on the samplers (e.g., West Town, West-Town, Weston) follow a pattern? The answer to the last question is no. It seems neither time period nor type of sampler dictated the spelling of the school name on a piece.

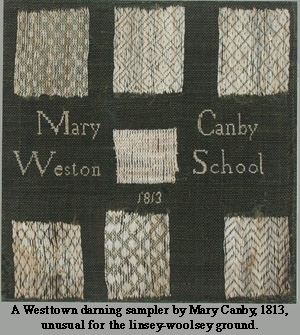

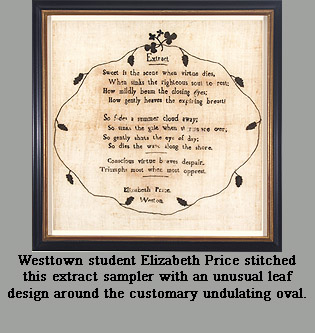

Some two hundred years after the opening of Westtown, there still is a plentiful body of needlework samplers made by Westtown girls that examined as a whole offers a window into the sewing school at Westtown. A look at over 260 samplers positively identified as made by students while at Westtown (about a third of which are in the school’s collection) suggests what may have transpired in that classroom so long ago. Was there a particular order in which the different types of samplers were made by a student? Was there a type of sampler made most often? Did styles change over the decades that sewing was part of the curriculum? And that ever vexing question: Does the use of variant spellings of the school name on the samplers (e.g., West Town, West-Town, Weston) follow a pattern? The answer to the last question is no. It seems neither time period nor type of sampler dictated the spelling of the school name on a piece. Activities in the sewing school were clearly intertwined with the school’s overall curriculum. (The course of studies was much the same for boys and girls at Westtown, though boys studied surveying while girls had lessons in sewing.) Darning and marking (alphabet) samplers are evidence of the Quaker vision of a useful education, offering girls practice in needlework skills employed for invisible mending as well as marking linens at home. Extract samplers with their pious and moral verses were part of the spiritual formation of the students. Students were not allowed to bring any books to school, so all literature available to them (from which these verses likely were selected) was approved by the committee overseeing the school. In the classroom and through needlework, girls were introduced to authors whose works would improve their literacy while providing spiritual inspiration and reflection. Nineteenth-century book lists and catalogues – and the rare books themselves – currently in the Westtown School archives confirm this link between the sewing activities of the girls and literary works used for lessons in reading and grammar.

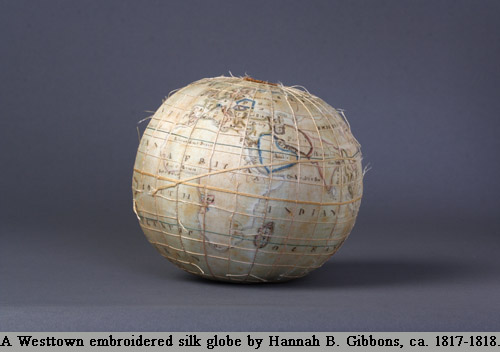

Activities in the sewing school were clearly intertwined with the school’s overall curriculum. (The course of studies was much the same for boys and girls at Westtown, though boys studied surveying while girls had lessons in sewing.) Darning and marking (alphabet) samplers are evidence of the Quaker vision of a useful education, offering girls practice in needlework skills employed for invisible mending as well as marking linens at home. Extract samplers with their pious and moral verses were part of the spiritual formation of the students. Students were not allowed to bring any books to school, so all literature available to them (from which these verses likely were selected) was approved by the committee overseeing the school. In the classroom and through needlework, girls were introduced to authors whose works would improve their literacy while providing spiritual inspiration and reflection. Nineteenth-century book lists and catalogues – and the rare books themselves – currently in the Westtown School archives confirm this link between the sewing activities of the girls and literary works used for lessons in reading and grammar.  The embroidered globes were perhaps more about lessons in geography and astronomy than needlework. Quaker education has long included an emphasis on the natural sciences for both practical and spiritual reasons because the better one understands the physical world and its workings, the better one knows the Creator. Despite the volume of student letters, committee minutes, and other documents in the school archives, no information has been discovered pointing to the conception of the fabric globes at Westtown. But what is known about the school’s curriculum during its early years makes it plausible that a teacher (or teachers) – or perhaps an ambitious student – determined that girls could and should make silk embroidered globes, both terrestrial and celestial. Through this exercise, girls not only studied the locations of continents and countries, stars and planets, and the relationship of earth and sky, but they made their own tools to do so. Globe-making is one area of Westtown’s sewing school not influenced by Ackworth or York School. Map samplers were worked at those English schools, but there is no evidence that embroidered globes were made.

The embroidered globes were perhaps more about lessons in geography and astronomy than needlework. Quaker education has long included an emphasis on the natural sciences for both practical and spiritual reasons because the better one understands the physical world and its workings, the better one knows the Creator. Despite the volume of student letters, committee minutes, and other documents in the school archives, no information has been discovered pointing to the conception of the fabric globes at Westtown. But what is known about the school’s curriculum during its early years makes it plausible that a teacher (or teachers) – or perhaps an ambitious student – determined that girls could and should make silk embroidered globes, both terrestrial and celestial. Through this exercise, girls not only studied the locations of continents and countries, stars and planets, and the relationship of earth and sky, but they made their own tools to do so. Globe-making is one area of Westtown’s sewing school not influenced by Ackworth or York School. Map samplers were worked at those English schools, but there is no evidence that embroidered globes were made.

As with most Westtown samplers, medallion ones were derived from the needlework traditions of English Quaker schools. Sarah (Tuke) Grubb penned the following about instructing girls in needlework at York School, “And whilst careful attention is paid to their improvement in necessary needlework & knitting, all that’s thought merely ornamental is uniformly discouraged.”

As with most Westtown samplers, medallion ones were derived from the needlework traditions of English Quaker schools. Sarah (Tuke) Grubb penned the following about instructing girls in needlework at York School, “And whilst careful attention is paid to their improvement in necessary needlework & knitting, all that’s thought merely ornamental is uniformly discouraged.”

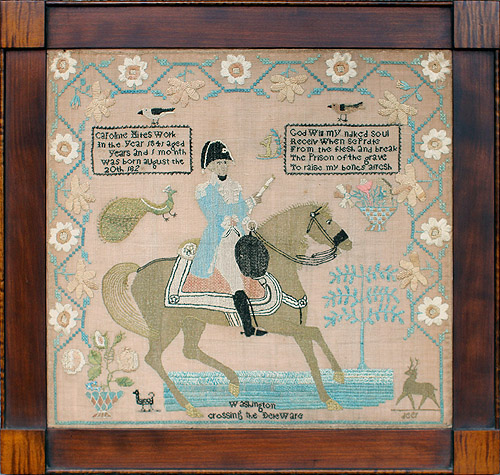

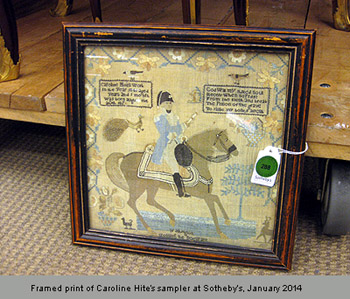

Additionally, the book, Samplers, by Susan Mayor and Diana Fowle, part of the Poster Art Series (Studio Editions LTD, London, 1990), included a large format print of Caroline Hite’s sampler as plate 35 (photo courtesy of Christie’s, New York). Over the years, we have seen many instances of pages from this Poster Art Series book framed and hung on a wall as if they were indeed samplers. These printed images measure anywhere from 8 to 11 inches in each dimension and when framed, can be somewhat effective.

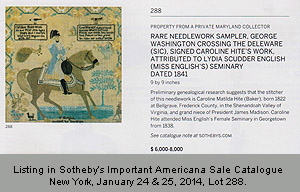

Additionally, the book, Samplers, by Susan Mayor and Diana Fowle, part of the Poster Art Series (Studio Editions LTD, London, 1990), included a large format print of Caroline Hite’s sampler as plate 35 (photo courtesy of Christie’s, New York). Over the years, we have seen many instances of pages from this Poster Art Series book framed and hung on a wall as if they were indeed samplers. These printed images measure anywhere from 8 to 11 inches in each dimension and when framed, can be somewhat effective. Flash forward to January, 2014: Sotheby’s Important Americana auction included as lot 288 in their printed catalogue Caroline Hite’s extraordinary sampler, and I was absolutely delighted to see that it was back on the market. Rather than classifying it as the Pennsylvania sampler that it is, it gained some misinformation: the assigned genealogy to a Virginia maker and attribution to a school in Georgetown, District of Columbia. Notwithstanding the erroneous reference, it was Caroline’s sampler. At the time, I was committed to be the successful bidder at the upcoming auction. I made arrangements to view the sampler prior to the public opening of the auction preview, precisely to examine it closely and to get my ducks in a row for the sale. I took a train to New York a few days after the New Year holiday and then a taxi to Sotheby’s. My unhappy assessment and disappointment upon seeing it in person was immediate – it was a framed page of the poster art book! Much smaller than the actual sampler, it measured 9 inches square (the catalogue included this measurement in their description but I assumed that this was a typo).

Flash forward to January, 2014: Sotheby’s Important Americana auction included as lot 288 in their printed catalogue Caroline Hite’s extraordinary sampler, and I was absolutely delighted to see that it was back on the market. Rather than classifying it as the Pennsylvania sampler that it is, it gained some misinformation: the assigned genealogy to a Virginia maker and attribution to a school in Georgetown, District of Columbia. Notwithstanding the erroneous reference, it was Caroline’s sampler. At the time, I was committed to be the successful bidder at the upcoming auction. I made arrangements to view the sampler prior to the public opening of the auction preview, precisely to examine it closely and to get my ducks in a row for the sale. I took a train to New York a few days after the New Year holiday and then a taxi to Sotheby’s. My unhappy assessment and disappointment upon seeing it in person was immediate – it was a framed page of the poster art book! Much smaller than the actual sampler, it measured 9 inches square (the catalogue included this measurement in their description but I assumed that this was a typo). The fact that it was a print not a sampler had somehow escaped the Sotheby staff. I broke the news to them and they saw the problem immediately; they removed the “sampler” from the upcoming sale. In fact, before my train returned to Philadelphia, Sotheby’s pulled this lot from their online version of the auction’s catalogue.

The fact that it was a print not a sampler had somehow escaped the Sotheby staff. I broke the news to them and they saw the problem immediately; they removed the “sampler” from the upcoming sale. In fact, before my train returned to Philadelphia, Sotheby’s pulled this lot from their online version of the auction’s catalogue.

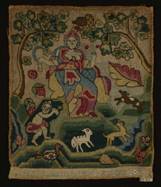

Mary Louisa Thomas (1819 – 1855) employed a wide variety of needlework stitches to create this elaborate pictorial sampler in 1832. She also included her family members in the cartouche. Her parents were Jesse and Alice (Levis) Thomas of East Goshen Township, ChesterCounty. Her brother and sisters were Gulielma Maria, Hannah Levis, and Eli Thomas. Hannah and Eli died before the sampler was completed and the black stitching around their names denotes that. None of the siblings, including the maker, lived beyond age 41. Gulielma was the only one who married. Mary attended WesttownSchool from October 1835 to February 1836. This sampler is typical of those made by girls who studied with Elizabeth Passmore, a teacher in EastGoshenTownship. (CCHS)

Mary Louisa Thomas (1819 – 1855) employed a wide variety of needlework stitches to create this elaborate pictorial sampler in 1832. She also included her family members in the cartouche. Her parents were Jesse and Alice (Levis) Thomas of East Goshen Township, ChesterCounty. Her brother and sisters were Gulielma Maria, Hannah Levis, and Eli Thomas. Hannah and Eli died before the sampler was completed and the black stitching around their names denotes that. None of the siblings, including the maker, lived beyond age 41. Gulielma was the only one who married. Mary attended WesttownSchool from October 1835 to February 1836. This sampler is typical of those made by girls who studied with Elizabeth Passmore, a teacher in EastGoshenTownship. (CCHS)

The Delaware Schoolgirl Sampler project is a newly funded collaborative effort designed to locate, document, interpret, disseminate, and promote awareness of historic schoolgirl samplers and related girlhood embroideries stitched in Delaware or residing in Delaware’s public and private collections. The project is funded, in part, by a grant from the Delaware Humanities Forum to the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture at the University of Delaware, and is the most recent initiative of the Sampler Archive Project (

The Delaware Schoolgirl Sampler project is a newly funded collaborative effort designed to locate, document, interpret, disseminate, and promote awareness of historic schoolgirl samplers and related girlhood embroideries stitched in Delaware or residing in Delaware’s public and private collections. The project is funded, in part, by a grant from the Delaware Humanities Forum to the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture at the University of Delaware, and is the most recent initiative of the Sampler Archive Project (

Mary Elizabeth Penton stitched her sampler in 1839 when her family lived in Brandywine Springs, New Castle County. She included many floral motifs and stitched two verses often found on samplers, "Teach Me to Feel Another's Woes…" and "I sigh not for beauty…" Little is known about her life prior to her marriage in the mid-1840s to another Brandywine Springs resident, Nathan Hiram Yearsley, the son of a blacksmith. The family remained in Delaware until about 1852, then moved to Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, before settling in Marshall Township, Taylor County, Iowa, by 1885, where Nathan and Thomas, the couple's oldest son, farmed. Nathan died in 1890 and Mary Elizabeth and son Thomas remained in Iowa for another fifteen years. In 1906 Mary Elizabeth, Thomas, and Thomas' niece and nephew relocated to the province of Alberta, Canada, where they obtained a homestead under the Dominion Lands Act. Thomas improved the property and farmed. Mary Elizabeth Penton Yearsley died in 1911 and Thomas followed the next year. They are both buried in Highwood Cemetery in High River, Alberta, Canada.

Mary Elizabeth Penton stitched her sampler in 1839 when her family lived in Brandywine Springs, New Castle County. She included many floral motifs and stitched two verses often found on samplers, "Teach Me to Feel Another's Woes…" and "I sigh not for beauty…" Little is known about her life prior to her marriage in the mid-1840s to another Brandywine Springs resident, Nathan Hiram Yearsley, the son of a blacksmith. The family remained in Delaware until about 1852, then moved to Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, before settling in Marshall Township, Taylor County, Iowa, by 1885, where Nathan and Thomas, the couple's oldest son, farmed. Nathan died in 1890 and Mary Elizabeth and son Thomas remained in Iowa for another fifteen years. In 1906 Mary Elizabeth, Thomas, and Thomas' niece and nephew relocated to the province of Alberta, Canada, where they obtained a homestead under the Dominion Lands Act. Thomas improved the property and farmed. Mary Elizabeth Penton Yearsley died in 1911 and Thomas followed the next year. They are both buried in Highwood Cemetery in High River, Alberta, Canada. Sarah Welsh (ca. 1820-?) is one of two known samplers from Miss Eliza Norris' school in "B Hundred" (Brandywine Hundred). She included Miss Norris' name and the abbreviated version of the school's location at the bottom on her sampler, along with the date 1831. Sarah stitched an alphabet in the four corners of the sampler, using a different font for each one. A floral vine occupies space at the bottom of the sampler, encasing Sarah's attribution, and another at the top provides a cover for eight lines from two different hymns. She stitched a large dog at the center of the sampler with a floral basket at each side.

Sarah Welsh (ca. 1820-?) is one of two known samplers from Miss Eliza Norris' school in "B Hundred" (Brandywine Hundred). She included Miss Norris' name and the abbreviated version of the school's location at the bottom on her sampler, along with the date 1831. Sarah stitched an alphabet in the four corners of the sampler, using a different font for each one. A floral vine occupies space at the bottom of the sampler, encasing Sarah's attribution, and another at the top provides a cover for eight lines from two different hymns. She stitched a large dog at the center of the sampler with a floral basket at each side. Samplers from Southern Boarding School

Samplers from Southern Boarding School

Louretta Downham (1833-1849) was born Louretta Fowler and came to the Downham family via an indenture. The Kent County Trustees of the Poor sent her to live with James Downham and his wife, Tamza (Tamsey) Downham in 1837 to learn "housewifery," when she was just four years old. They were required to provide a basic education for her, which seemed to have included needlework. Louretta died in 1849 at age fifteen, according to her tombstone, though other sources record her death as 1850. At the time of her death, she was living and working in the household of Samuel Broadway Cooper. She was buried in the Cooper Family Cemetery near the Kent County town of Petersburg, about five miles from the Craig farm. Louretta's tombstone is inscribed with her name, birth and death dates, and the notation that she was the "Adopted dau. of James Downham," though no confirmation of a legal adoption has been found.

Louretta Downham (1833-1849) was born Louretta Fowler and came to the Downham family via an indenture. The Kent County Trustees of the Poor sent her to live with James Downham and his wife, Tamza (Tamsey) Downham in 1837 to learn "housewifery," when she was just four years old. They were required to provide a basic education for her, which seemed to have included needlework. Louretta died in 1849 at age fifteen, according to her tombstone, though other sources record her death as 1850. At the time of her death, she was living and working in the household of Samuel Broadway Cooper. She was buried in the Cooper Family Cemetery near the Kent County town of Petersburg, about five miles from the Craig farm. Louretta's tombstone is inscribed with her name, birth and death dates, and the notation that she was the "Adopted dau. of James Downham," though no confirmation of a legal adoption has been found.

Eliza Marriner (1803-1881) made her sampler in 1817 and it is attributed to Mrs. Bowers' School. Her genealogical sampler provides detailed information about her family listed in two columns, their tops linked by a leafy vine. A tree stands next to the right column and more family details are stitched between it and the left column.

Eliza Marriner (1803-1881) made her sampler in 1817 and it is attributed to Mrs. Bowers' School. Her genealogical sampler provides detailed information about her family listed in two columns, their tops linked by a leafy vine. A tree stands next to the right column and more family details are stitched between it and the left column. Ann P. Burton worked a sampler in 1821, noting that it was made at "Mrs. Bower's School Lewes." It is a style that is very similar to several others from the school. She also included such family details as the names and marriage date for her parents, Cornelius and Sarah Burton, and the births, with dates, of her siblings. She noted the death dates of her father and brother John M. Following her father's death, her mother married Thomas Rodney, and Ann reported their marriage and the birth of their daughter, Ruth.

Ann P. Burton worked a sampler in 1821, noting that it was made at "Mrs. Bower's School Lewes." It is a style that is very similar to several others from the school. She also included such family details as the names and marriage date for her parents, Cornelius and Sarah Burton, and the births, with dates, of her siblings. She noted the death dates of her father and brother John M. Following her father's death, her mother married Thomas Rodney, and Ann reported their marriage and the birth of their daughter, Ruth.  Elizabeth West Carpenter made her sampler under the direction of Mrs. Thopson in 1831. Her sampler includes a bounty of family information, though some is recorded with initials. She includes her parents' and sibling's information. Three of her siblings were married at the time Elizabeth stitched her sampler; she listed their spouses, and for one sister, the initials of her four children.

Elizabeth West Carpenter made her sampler under the direction of Mrs. Thopson in 1831. Her sampler includes a bounty of family information, though some is recorded with initials. She includes her parents' and sibling's information. Three of her siblings were married at the time Elizabeth stitched her sampler; she listed their spouses, and for one sister, the initials of her four children.

Appendices, compiled by Susi B. Slocum and Sheryl De Jong, of known needlework, teachers and schools, and needlework entries from Young Ladies’ Academy ledgers follow the narrative.

Appendices, compiled by Susi B. Slocum and Sheryl De Jong, of known needlework, teachers and schools, and needlework entries from Young Ladies’ Academy ledgers follow the narrative.

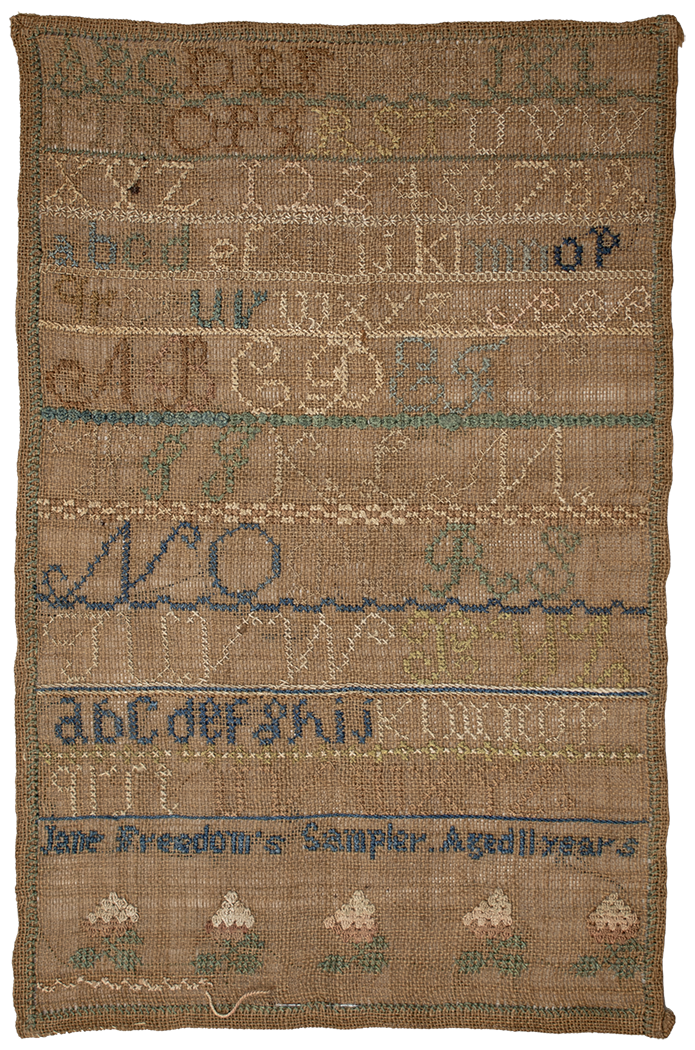

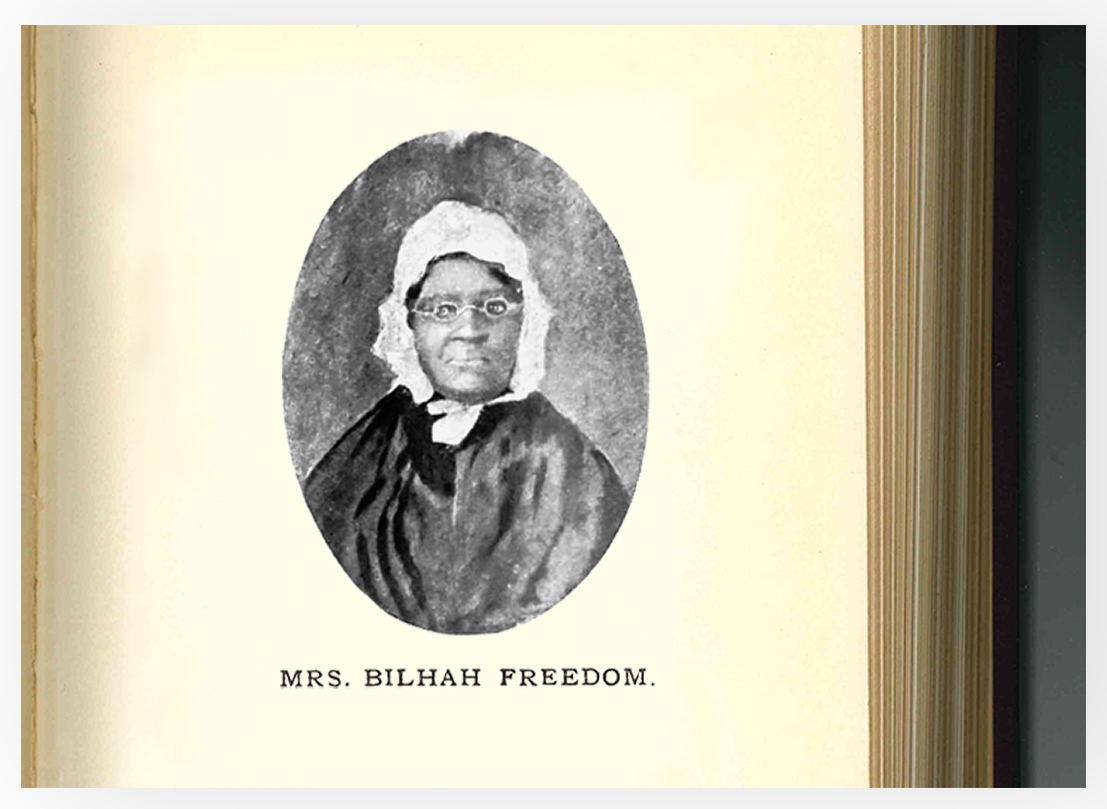

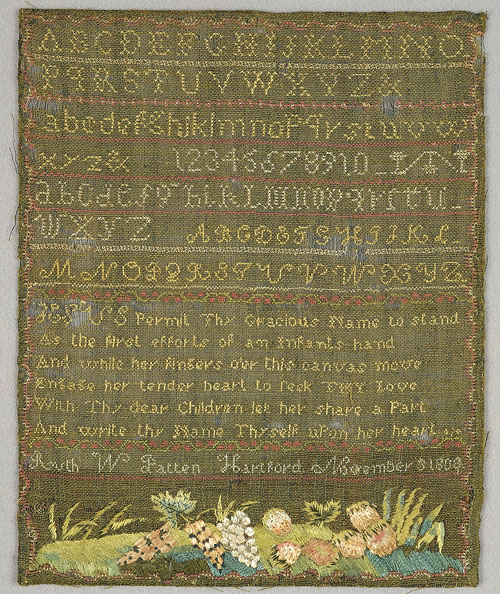

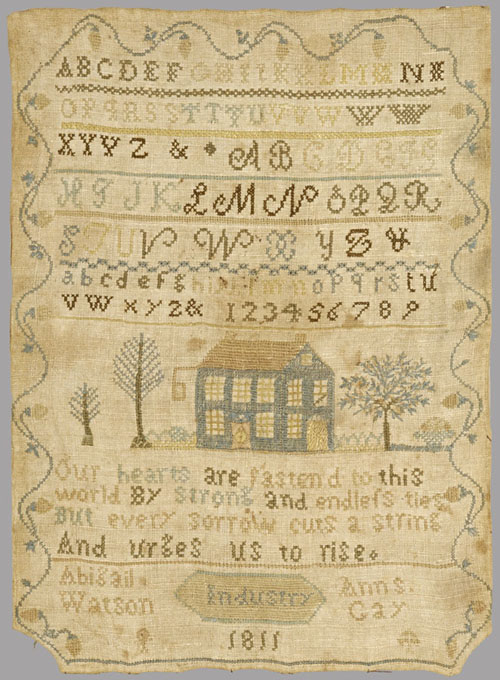

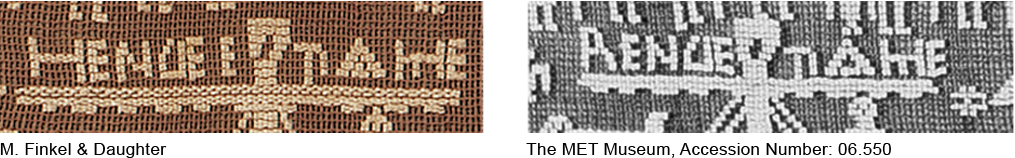

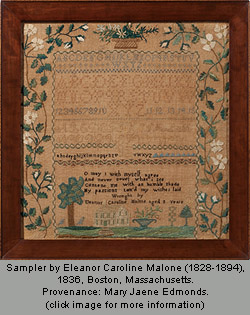

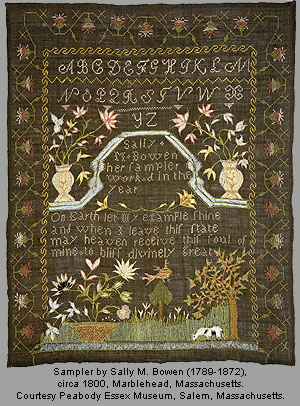

Malone was not alone in removing age-identifying information from her girlhood sampler. Recent research for A Stitch In Time: The Needlework of Aging Women in Antebellum America identified twenty-eight such samplers.10 These samplers are generally in good condition with just a few numbers missing in key spots; they are not suffering from deterioration throughout, nor do they have tears or rips that have rendered them illegible. The missing numbers are clearly the conscious work of the maker or another person. Take, for example, the sampler made by Sally M. Bowen (1789-1872) of Marblehead, Massachusetts.11

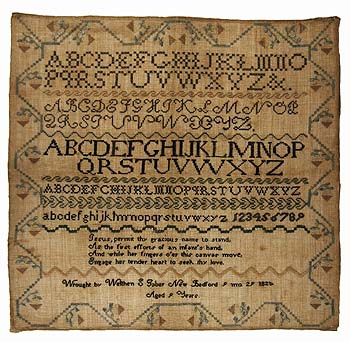

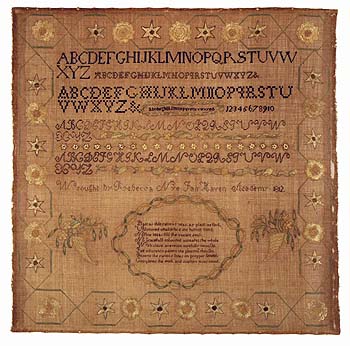

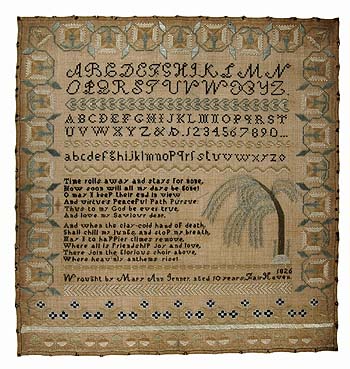

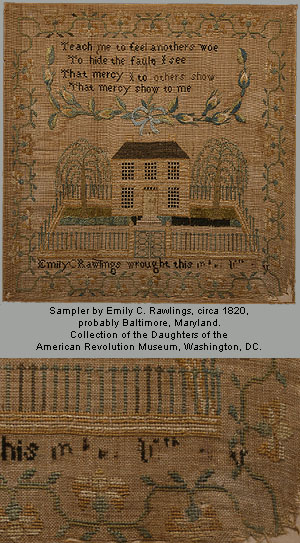

Malone was not alone in removing age-identifying information from her girlhood sampler. Recent research for A Stitch In Time: The Needlework of Aging Women in Antebellum America identified twenty-eight such samplers.10 These samplers are generally in good condition with just a few numbers missing in key spots; they are not suffering from deterioration throughout, nor do they have tears or rips that have rendered them illegible. The missing numbers are clearly the conscious work of the maker or another person. Take, for example, the sampler made by Sally M. Bowen (1789-1872) of Marblehead, Massachusetts.11 In this group of twenty-eight samplers, almost half (13) were altered by having part of all of the year the sampler was originally made picked out. Another eleven samplers were altered by having part or all of the maker’s age or birth year picked out. Three samplers were altered by especially determined women; they have part or all of both the age or birth year and the year the sampler was made removed. And, one sampler had stitching picked out, but it is unclear what the missing information conveyed. In many cases – seventeen out of the twenty-eight samplers identified – these alterations, designed to conceal information, remain successful today despite the wide accessibility of genealogical records at research libraries and on the internet. Without crucial bits of information such as the maker’s birth year or age in a particular year, the lives of these makers cannot be traced, particularly when there is more than one girl with the same name born around the same time. For example, the sampler made by Emily C. Rawlings (dates unknown) cannot be conclusively identified or dated today.13

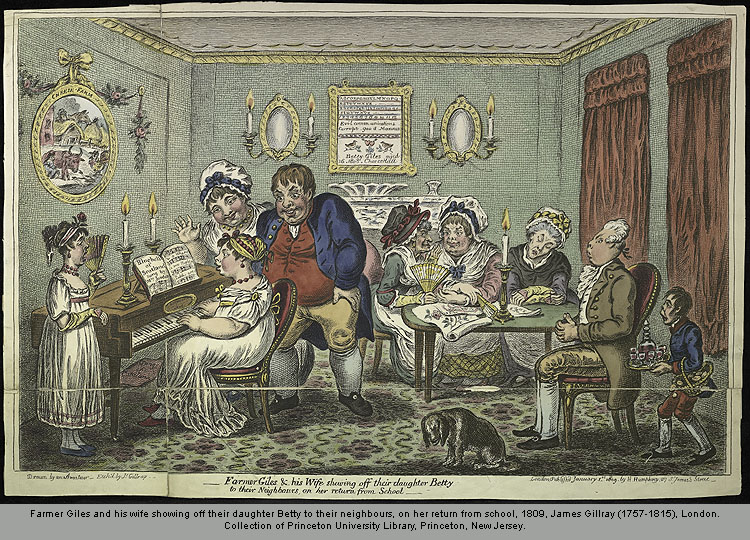

In this group of twenty-eight samplers, almost half (13) were altered by having part of all of the year the sampler was originally made picked out. Another eleven samplers were altered by having part or all of the maker’s age or birth year picked out. Three samplers were altered by especially determined women; they have part or all of both the age or birth year and the year the sampler was made removed. And, one sampler had stitching picked out, but it is unclear what the missing information conveyed. In many cases – seventeen out of the twenty-eight samplers identified – these alterations, designed to conceal information, remain successful today despite the wide accessibility of genealogical records at research libraries and on the internet. Without crucial bits of information such as the maker’s birth year or age in a particular year, the lives of these makers cannot be traced, particularly when there is more than one girl with the same name born around the same time. For example, the sampler made by Emily C. Rawlings (dates unknown) cannot be conclusively identified or dated today.13 Decorative schoolgirl samplers like the ones identified here were made to be framed and hung proudly on the wall of the family parlor. Countless newspaper ads from the early nineteenth century offered frames specifically to display needlework.18 An English cartoon from 1809 (image below) shows the prominent placement of one girl’s framed sampler in her parents’ parlor; the same tradition was followed in America.19 Sarah Anna Smith Emery (1787-1879) of Newbury, Massachusetts, remembered that “One was considered very poorly educated who could not exhibit a sampler; some of these were large and elaborate specimens of handiwork; framed and glazed, they often formed the chief ornament of the sitting room or best parlor.”20 In 1858, twelve-year-old Susan Bradford Eppes (1846-1942) noted in her diary “This is Father’s Birthday and my picture of The Temple of Time was ready for him. He was pleased and surprised. It is prettily framed and is hanging on the Library wall.”21 While continuing to showcase a woman’s skill with the needle and her familiarity with the elements of a genteel lifestyle, by the time she entered her forties and beyond the sampler also continued to proclaim its maker’s age to all who entered the parlor.

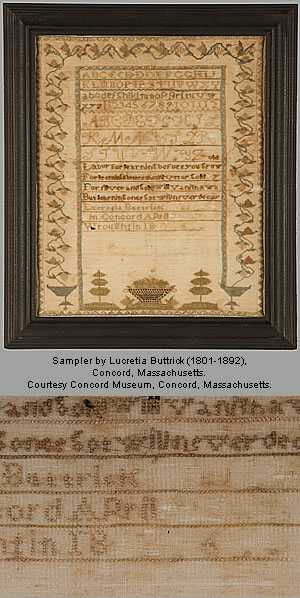

Decorative schoolgirl samplers like the ones identified here were made to be framed and hung proudly on the wall of the family parlor. Countless newspaper ads from the early nineteenth century offered frames specifically to display needlework.18 An English cartoon from 1809 (image below) shows the prominent placement of one girl’s framed sampler in her parents’ parlor; the same tradition was followed in America.19 Sarah Anna Smith Emery (1787-1879) of Newbury, Massachusetts, remembered that “One was considered very poorly educated who could not exhibit a sampler; some of these were large and elaborate specimens of handiwork; framed and glazed, they often formed the chief ornament of the sitting room or best parlor.”20 In 1858, twelve-year-old Susan Bradford Eppes (1846-1942) noted in her diary “This is Father’s Birthday and my picture of The Temple of Time was ready for him. He was pleased and surprised. It is prettily framed and is hanging on the Library wall.”21 While continuing to showcase a woman’s skill with the needle and her familiarity with the elements of a genteel lifestyle, by the time she entered her forties and beyond the sampler also continued to proclaim its maker’s age to all who entered the parlor. Lucretia Buttrick’s (1801-1892) sampler, originally stitched in the 1810s, was altered later in its life when her age was removed. And, Buttrick was not exact about her age on the U.S. Census as she grew older. In 1850, she was listed as forty-nine years old – her correct age – but in 1860, she was listed as fifty-three years old, six years younger than she actually was. In 1870, she gave her age as fifty-eight, eleven years less than her true age.25 In his study of the history of aging in America, David Hackett Fischer discovered that a certain type of “age heaping,” providing an incorrect age to the census taker, increased on late-nineteenth century census returns. During the eighteenth century, it was quite common for people to round off their ages to end in a five or a zero because they either did not know how old they were, or did not care. However, Fischer found that as literacy increased, this kind of age heaping decreased; instead, people pretended to be younger than they were. He asserts that it was most common for men in their forties and fifties to lie about their age on the census, but the large number of samplers with picked out ages and years suggests that women were equally conscious of their age in the mid-nineteenth century.26

Lucretia Buttrick’s (1801-1892) sampler, originally stitched in the 1810s, was altered later in its life when her age was removed. And, Buttrick was not exact about her age on the U.S. Census as she grew older. In 1850, she was listed as forty-nine years old – her correct age – but in 1860, she was listed as fifty-three years old, six years younger than she actually was. In 1870, she gave her age as fifty-eight, eleven years less than her true age.25 In his study of the history of aging in America, David Hackett Fischer discovered that a certain type of “age heaping,” providing an incorrect age to the census taker, increased on late-nineteenth century census returns. During the eighteenth century, it was quite common for people to round off their ages to end in a five or a zero because they either did not know how old they were, or did not care. However, Fischer found that as literacy increased, this kind of age heaping decreased; instead, people pretended to be younger than they were. He asserts that it was most common for men in their forties and fifties to lie about their age on the census, but the large number of samplers with picked out ages and years suggests that women were equally conscious of their age in the mid-nineteenth century.26