Take your needle, my child, and work at your pattern; it will come out a rose by and by.

Oliver Wendell Holmes

As long as I can remember, I have been drawn to things historical. As a child I imagined myself becoming an archaeologist. Whilst that didn’t happen, my preoccupation with the past manifested itself in other ways including my love of genealogical research and of collecting hand-made antiques – those often simple or primitive one-of-a-kind survivors that are a reflection of their makers’ creative efforts. Those two passions intersect in the rare instances when I have been able to acquire a treasured antique of Irish origin.

Owing at least in part to centuries of economic, religious and societal oppression experienced by the people of Ireland, Irish antiques are not routinely found at public sale in large numbers. Fortunately, the long-standing commitment of the Irish people to historic preservation allows us to see Irish antiques in museums and other public venues. In the open market, Irish antiques with unquestionable provenance such as hallmarked Irish silver or jewelry command understandably high prices when available. My interest doesn’t lie in those things. I am drawn to the things that represent the remnants of the lives of the majority of Irish who were our ancestors. Those things, often called “folk art” in the antiques trade, are scarce due to their fragile nature or purely utilitarian purpose but, when found, offer us the opportunity to connect with our Irish past in a more personal way. If we are so fortunate as to be able to identify the maker or source of such an object, its resonance is amplified and the connection made even more meaningful and informative.

In a three-part series in the April, May and June issues of Irish Lives Remembered, I want to introduce you to Jane Gage, Eliza Woods and Anne Walpole, girls who grew up in Ireland in the late 18th to mid-19th centuries. In their youth, each put needle and thread to fabric to practice their stitch-work by creating an embroidered sampler that included the alphabet, numbers, and/or verse with a religious or moral theme. Sampler-making was an important educational activity for young girls in Europe and America for centuries in environments as diverse as exclusive boarding academies, country day schools, and even orphanages or other charitable institutions. Despite similarities in form or content, each surviving example is a unique expression of the individual maker created under the guiding hand of her instructor.

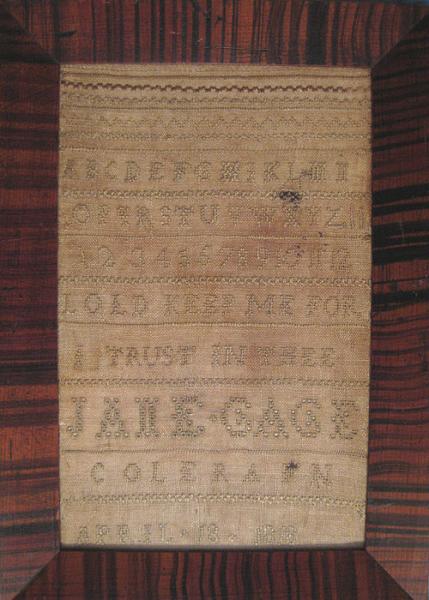

Part One: Jane gage – “Lord Keep me for I trust in Thee”

Jane dated her sampler April 18, 1818 in addition to embroidering her name and location: “Colerain,” giving us key information about her identity. Now nearly two centuries old and quite faded, Jane’s needlework on linen measures about 8 by 12 inches and includes rows of various practice stitches at the top and also separating the lines of alphabet letters, numbers and verse. As is not uncommon with schoolgirl samplers, Jane’s work has an error: a misspelling of the word “LORD” as “LOLD.” No matter that. We all know what little Jane meant to say.

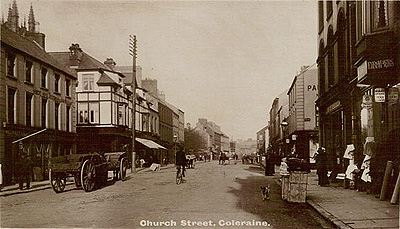

My basic historical and genealogical research revealed that Coleraine was both a town and a barony in then County Londonderry and a locale well-known for its linen production and exports as well as for the salmon harvested from the River Bann and dispatched via ship to Liverpool, Glasgow and beyond. Coleraine was a long-time area of residence for a number of Gage families, particularly in the parishes of Killowen, Dunhoe, Macosquin and Aghadowey. In addition to the Gage descendants who remained in Ireland, I found two lines, one Canadian and one in the southern U.S. that each traces its lineage back to the Gages of Coleraine. As anyone doing genealogical research knows, following male surname descent, while not necessarily easy, presents less of a challenge than searching the weeds for the females of the same family. In Jane’s case, I can say that the Christian name “Jane” is found in multiple generations of the Gage family in the 18th and 19th centuries. I also found an 1859 Griffith’s Valuation record for the Town of Coleraine, Parish of Killowen, listing a Jane Gage as the occupier of a house and yard on Killowen Street, and as the lessor of a house on an adjacent property. Could that be the same Jane Gage who wrought her sampler there forty years earlier? Since I acquired Jane’s sampler in the U.S., it could be just as likely that she was among the Gages who emigrated to North America in the 1800s. The important thing is that 195 years later, this small piece of Jane remains as a reminder of a young Ulstergirl and a life that can still pique our curiosity and imagination.

Part two – Eliza Woods of Pettigo

I cannot count my day complete, ‘til needle, thread, and fabric meet. Unknown

In this second part of a three-part series in the April, May and June issues of Irish Lives Remembered, we explore the work of another young Irish sampler-maker, Eliza Woods, a student in Pettigo in County Donegal who was learning that craft as Ireland was experiencing the dark years of the Great Famine.

In their youth, young girls put needle and thread to fabric to practice their stitch-work by creating an embroidered sampler that included the alphabet, numbers, and/or verse with a religious or moral theme. Sampler-making was an important educational activity for young girls in Europe and America for centuries in environments as diverse as exclusive boarding academies, country day schools, and even orphanages or other charitable institutions. Despite similarities in form or content, each surviving example is a unique expression of the individual maker created under the guiding hand of her instructor.

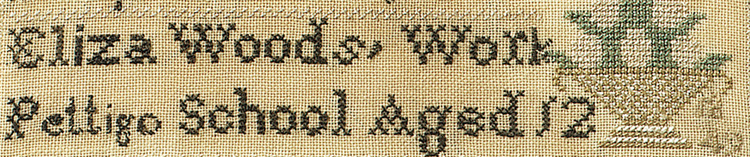

Eliza Woods – “. . . there is laid up for me a crown which cannot fade”

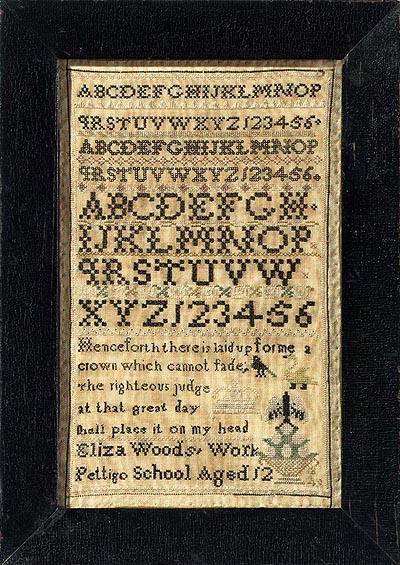

Eliza Woods’s needlework tells us that she was 12 years old and a student at the Pettigo School when she wrought her sampler. Thankfully, and perhaps as an afterthought, Eliza squeezed in the year she completed her sampler (1849) at the lower right edge of the piece. That key item of information in combination with her age points to her having been born in 1837 or 1836.

Eliza’s sampler, measuring about 7 by 11.5 inches and still bright and without holes, soiling or water-stains, must have remained a treasured item as it passed through the hands of a succession of owners over the last 164 years. The rows of alphabet letters and numbers bordered with geometric elements showcase her proficiency in embroidering a variety of stitch types and sizes with delicate precision. The sampler is further ornamented with an urn on which a butterfly had alighted (upside down) along with a swan, small black bird and a crown (most likely a reference to the English monarchy). Below that is the following religious verse:

“Henceforth there is laid up for me a crown which cannot fade; the righteous judge at that great day shall place it on my head.”

According to the 1846 edition of Slater’s Commercial Directory of Ireland, Pettigo was “a small market town” near Lower Lough Erne sitting partially in County Donegal and partly in County Fermanagh with a “small stream” dividing the little town and the two counties. The description went on to call the local countryside “romantic and picturesque” while saying that the town had very little trade going on but for that connected to fairs and the local market. Local religious institutions included Roman Catholic, Presbyterian, Wesleyan Methodist, Primitive Methodist and what was simply referred to as the Parish Church (presumably Church of Ireland). Slater’s listed a resident surgeon, land surveyor, constable and local tradespeople including a carpenter, butcher, saddler, ironmonger, baker, and a cooper along with multiple blacksmiths, grocers, drapers, shoemakers and tailors. Pettigo also had an active mill powered by a local waterfall.

In the mid-19th century Pettigo was also home to two schools, the Parochial School under the direction of James Copeland and Mary Copeland, listed as the master and mistress of that school, and the National School where John McAffery served as master. Eliza worked her sampler while a student at one of those schools. The Griffith’s Valuation of 1857 listed a James Woods living on Mill Streetin Pettigo, a tenant renting house and yard from the Leslie family, prominent owners of large land holdings in the area. There is also a James Woods interred in the Templecarne Graveyard in Pettigo, having died there at the age of 83 in 1889, very possibly the same man. Could James have been Eliza’s father or other family member? I cannot say.

As much as I would like to be able to answer that question, that’s not what I think about when I look at Eliza’s lovely 1849 sampler. Each time I admire her work, I wonder that such a beautiful thing was lovingly and painstakingly created at a time when Ireland was in the grip of the tragic Great Famine and I think how fortunate Eliza must have been as compared to so many other Irish children who, with their dispossessed and starving families, were among hundreds of inmates at one of the nearby Poor Law Union Workhouses in Donegal at the very same time.

Part three – Anne Walpole of Clonmel

All my scattering moments are taken up with my needle.

Ellen Birdseye Wheaton– 1851

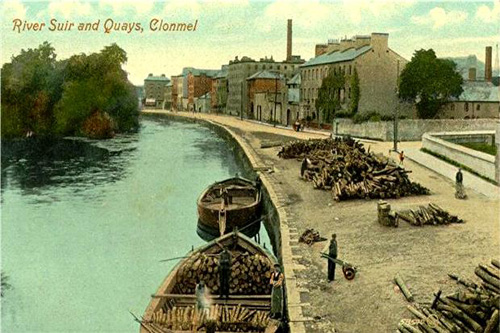

In this third part of a three-part series in the April, May and June issues of Irish Lives Remembered, we meet a third young Irish sampler-maker, Anne Walpole, who worked her sampler at the Clonmel School in County Tipperary in the last decade of the 18th century.

In their youth, young girls put needle and thread to fabric to practice their stitch-work by creating an embroidered sampler that included the alphabet, numbers, and/or verse with a religious or moral theme. Sampler-making was an important educational activity for young girls in Europe and America for centuries in environments as diverse as exclusive boarding academies, country day schools, and even orphanages or other charitable institutions. Despite similarities in form or content, each surviving example is a unique expression of the individual maker created under the guiding hand of her instructor.

Anne Walpole – “That gracious pow’r, who from his kindred clay, Bids man arise to tread the realms of day.”

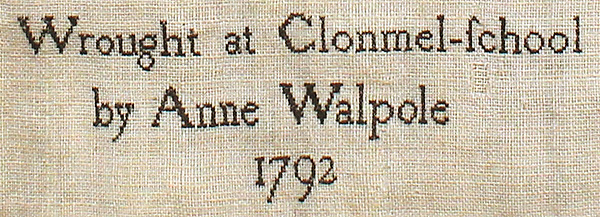

Anne Walpole worked her religious verse sampler in 1792 at the Clonmel School in a traditional Quaker style. My research on Anne and her sampler started with searches on the internet to learn about the Clonmel Quaker School and to try to find public genealogical information about the Walpole family.

Those efforts proved fruitful and led me to a Walpole descendant (Peter Walpole) in Australia and an early photo of a Walpole family residence in what was then Queens County (now County Laois). In addition, I found a very interesting 1990 article titled “The Quaker Schools in Clonmel,” written by Irish historian Michael Ahern that had appeared in the Tipperary Historical Journal. I was able to contact Mr. Ahern by email and he graciously provided me with his insights. I also wrote to the Friends Historical Library in Dublin. Christopher Moriarty, Curator at the Library, responded and generously included information on the Walpoles from their extensive database. But my global journey was not over yet. Peter Walpole suggested I contact Christopher Walpole for further assistance. (Reverend) Christopher Walpole, who lives in Northern Ireland, was also quick to respond to my inquiry and offered any assistance he could provide since he was descended of Anne Walpole’s brother William!

The foregoing illustrates what we family history detectives call “acts of genealogical kindness” - those serendipitous connections that light the way to additional discoveries and enrich the outcome of our efforts. My sincere thanks to Peter Walpole, Christopher Moriarty, Michael Ahern and Christopher Walpole for their contributions to the telling of Anne Walpole’s story.

So, who was Anne Walpole? Anne was born in Carrowreagh, Queens County in 1778, the oldest of six children and the only daughter born to William and Jane (Lecky) Walpole, residing at Mondrehid House. The Walpoleswere Quakers, members of the Society of Friends, Mountmellick Meeting. Anne’s father and her brothers were “gentlemen farmers” who owned and leased lands in Carrowreagh (Parish of Aghaboe) and Mondrehid (Parish of Offerlane) according to Tithe Applotment and Griffith’s Valuation records.

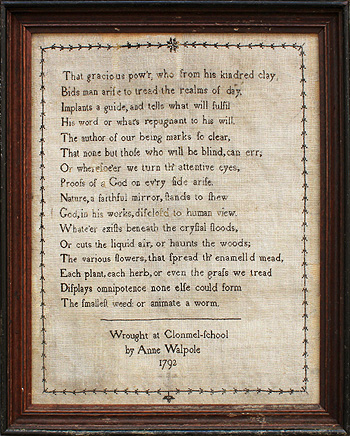

The SuirIsland Quaker School where Anne attended classes was a boarding and finishing school for girls established in 1787 in Clonmel in County Tipperary by prosperous Quaker missionaries and philanthropists Robert and Sarah Tuke Grubb. Studies included foreign languages, science, literature and religion along with the expected classes in drawing and needlework with an overall emphasis on the disciplines of the Quaker lifestyle. Anne Walpole’s 1792 embroidery sampler, measuring about 9 by 12 inches, was worked at the Clonmel School when she was a 14-year-old student there.

Anne’s sampler is a representative example of the simple Quaker form of the period. The first part of the religious verse celebrates the creative power of God that “authors” beings and provides a clear guide to fulfilling God’s will. The second part of the text paints beautiful imagery of the manifestation of God to man through the mirror of nature:

“Whatever exists beneath the crystal floods,

Or cuts the liquid air, or haunts the woods,

The various flowers that spread the enamelled mead,

Each plant, each herb, or even the grass we tread

Displays omnipotence none else could form

The smallest weed or animate a worm.”

Anne Walpole’s life was actually at its midpoint when she finished her sampler in 1792. She would die fifteen years later in 1807 in Carrowreagh at the young age of 29.

Over a half-century elapsed between the time Anne Walpole, Eliza Woods and Jane Gage worked their samplers, each of them living in times punctuated by the continuing political, economic and societal struggles in their Irish homeland even as they were receiving the benefits of an education. Anne Walpole was a student at the Clonmel Quaker School in the era of Theobold Wolfe Tone and the years leading up to the Rebellion of 1798. Jane Gage of Coleraine lived in the days when Daniel O’Connell, The Liberator, campaigned for repeal of the Act of Union. Eliza Woods was a schoolgirl in the dark years of the Great Famine, a catastrophic human tragedy that spawned the worldwide Irish Diaspora. Time is a great storyteller, indeed.