Connecticut Needlework: Women, Art, and Family, 1740-1840, on view at the Connecticut Historical Society in Hartford from October 6, 2010 through March 26, 2011, explores regional needlework production in unprecedented depth and variety. More than eighty works, drawn almost entirely from the CHS’s extensive collections, provide a varied and sometimes surprising survey of needlework produced in the state prior to 1840: colonial canvas-work, quilting, and crewel-embroidered bed hangings; Revolutionary-era bed rugs; elegant depictions of classical, religious, and memorial scenes embroidered in silk during the Federal era; early 19th-century family registers and white-work, and of course, samplers.

An entire gallery celebrates Connecticut sampler making, with more than forty examples exploring design and stitching traditions from families, schools, and towns throughout the state. Lucy Spalding’s 1793 sampler (fig. 1, at end of article) holds the distinction of being the first sampler to enter the CHS collection, donated by a Connecticut native striking out for the Far West two years before the opening shots of the Civil War, and six decades before Ethel Bolton and Eva Coe’s landmark publication, American Samplers. Lucy’s square shape and imaginatively compartmentalized design connect her work to an extended series of samplers made in and around the prosperous seaport town of Norwich, in southeastern Connecticut.

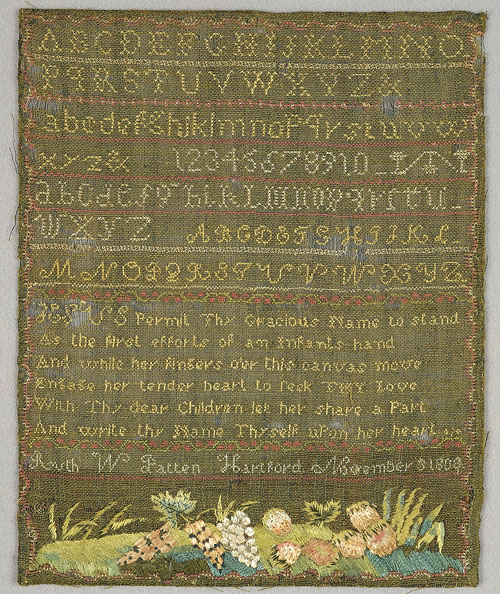

Ruth W. Patten’s 1808 sampler (fig. 2, at end of article) provides the first example of a sampler to be attributed to the Patten family school, taught in Hartford by Ruth’s three aunts, and better known for elegant silk embroidered coats of arms and allegorical and religious pictures. Ruth’s yellow and orange cross-stitches, set off by a green linsey-woolsey ground (linen and wool plain-weave), connect her work to a local tradition of samplers stitched in this color combination. The pictorial panel at the bottom of the sampler suggests that Ruth was just learning silk embroidery techniques, producing a simple display of carrots, grapes, and strawberries arrayed on a grassy hillock, stitched with a backing fabric of glazed brown cotton to reinforce the loosely woven ground in this area.

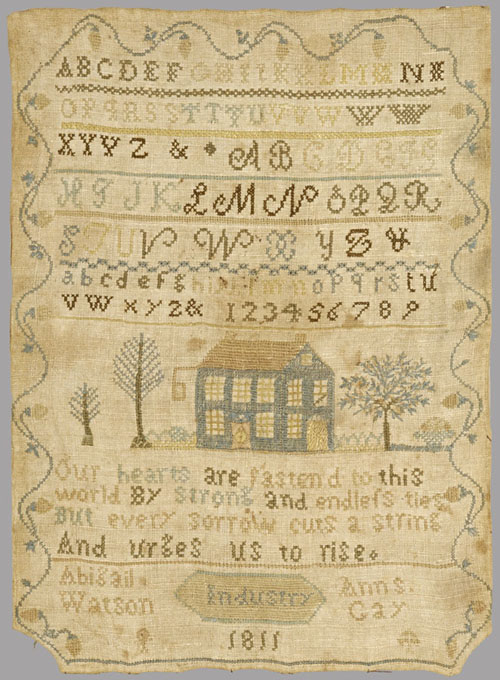

Two names appear on a delightful 1811 sampler from the northeastern-most Connecticut town of Thompson (fig. 3, at end of article): Abigail Watson and Ann S. Gay likely represent teacher and student, but incomplete biographical information has thus far made it impossible to ascertain which was which. The pictorial panel in the center of the composition suggests the influence of Newport house samplers, with the individualizing touches of a tavern sign hanging from one corner of the dwelling and an attic flight of stairs glimpsed through a second floor window.

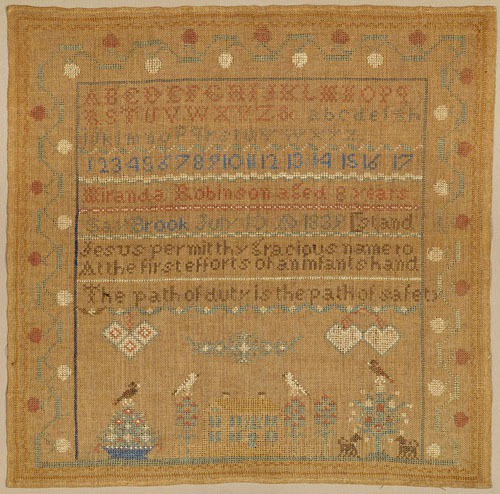

Miranda Robinson’s 1839 sampler (fig. 4, at end of article), one of the latest in the exhibition, is notable as an extremely rare example of decorative embroidery known to have been the work of a free black girl. Made in Long Island community of Saybrook (now Old Saybrook), it was preserved in the collection of noted twentieth-century author, Ann Petry, the first African American woman writer to sell over one million copies of a novel.

Three additional galleries complement the samplers, enriching understanding and appreciation by illuminating the long and varied regional needlework traditions from which individual sampler makers emerged. The exhibition opens with a gallery devoted to the work of earlier generations of Connecticut needleworkers, many of them the direct ancestors of the sampler makers. The CHS collections are particularly rich in pre-Revolutionary needlework, facilitating comparisons of familiar crewel embroidered bed hangings and canvaswork pocketbooks with less frequently seen genres, such as quilted petticoats and silk embroidered shoes.

A third gallery features silk embroidered pictures, with idealized pastoral visions of the mid-eighteenth-century succeeded by more literal neo-classical, Biblical, and literary scenes in the early nineteenth century. Several pictures represent Connecticut ’s three best-known girls schools: the Patten family school and Lydia Bull Royse’s school, both in Hartford, and Sarah Pierce’s school in the northwestern Connecticut town of Litchfield.

The final gallery presents needlework forms characterized by a shared concern for family identification – family registers, memorial pictures, and coats of arms. Mary Bidwell’s family register, ca. 1762, represents the earliest known American needlework example (predating by more than a decade the earliest previously recorded needlework specimen, also from the Hartford area). Family portrait memorials, a genre that Betty Ring associated strongly with Connecticut, are represented by three examples; the eleven headless figures in the unfinished Punderson family memorial offer a fascinating glimpse into the creative process.

Reinforcing the connections between needlework and family, the exhibition closes with an unprecedented celebration of needlework from several generations of the Punderson family of southeastern Connecticut. Prudence Punderson’s silk-embroidered allegorical picture, “The First, Second, and Last Scene of Mortality,” is by far the most frequently published object in CHS’s entire collection. It appears here not as a work as individual genius – which it undeniably is – but as the culminating achievement of several generations of talented needleworkers, the female equivalent of kinship-based workshop traditions in male-dominated trades such as woodworking and metalsmithing.

The exhibition is accompanied by a collection catalog of the same title, authored by Dr. Susan P. Schoelwer, former Director of Museum Collections at the Connecticut Historical Society and now Curator at George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Distributed by Wesleyan University Press, the volume is available from the University Press of New England ($ 65 cloth, $ 30 paper).

Two-page spreads for seventy catalog entries feature full-page illustrations of each of the selected works, accompanied by a page of text discussing each example and its maker (the vast majority of whom can be identified, thanks to strong family histories supported by extensive genealogical research). Photographs of stitches, reverse sides, sketches, design sources, and related works enhance understanding and appreciation of the samplers and other needlework genres.

Four major themes emerge from this study of Connecticut needlework: first, the vital contribution of needlework to the development of the visual arts in the region; second, the importance of multi-generational family traditions in disseminating and perpetuating needlework skills and designs, both before and after the widespread establishment of formal female academies in the Federal period; third, an unexpected correlation between needlework skills and advanced education (contrary to the popular notion that these two pursuits were antithetical, in early Connecticut the most skilled needleworkers were often among the most highly educated women of their time and place); and fourth, the gradual demographic diffusion of needlework (centered primarily among the clerical elite and their relations in the colonial period, then spreading to the daughters of small industrialists and entrepreneurs after the Revolution, and finally to the households of tradesmen and farmers in the ante-bellum period). These interpretive themes build upon the pioneering research of earlier needlework scholars (most notably the late Susan B. Swan, Glee Krueger, and Betty Ring) to suggest new approaches to future explorations of regional needlework, throughout early America.

A one-day symposium will be held at CHS on Saturday, October 30, featuring talks by catalog author Susan Schoelwer; Linda Baumgarten, Curator, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; Textile Conservator Dierdre Windsor; and Linda Eaton, Curator, Winterthur Museum. Please contact Mary Muller at CHS for further schedule and registration information ( http://store.chs.org/products/Needlework-Conference%3A-October-30%2C-2010.html ; telephone 860-236-5621).

Financial support for Connecticut Needlework has been provided by major grants from the Coby Foundation, Ltd., and the National Endowment for the Arts, and from generous sponsors, including M. Finkel & Daughter.

Susan P. Schoelwer

Author, Connecticut Needlework: Women, Art, and Family, 1740-1840

Curator, George Washington’s Mount Vernon Estate & Gardens

The author continues to assemble data on Connecticut needlework. Readers who own or know of examples are encouraged to send images and information, including genealogical research, to: spschoelwer@gmail.com .

Fig. 1. Lucy Spalding’s sampler, dated 1793, probably Plainfield, Connecticut

Courtesy of the Connecticut Historical Society, Gift of Hezekiah Lord Hosmer, 1859.18.2

Gift of Mrs. Theda Lundquist, 2001.29.0

Fig. 3. Industry sampler, signed by Abigail Watson and Ann S. Gay, dated 1811,Thompson, Connecticut

Courtesy of the Connecticut Historical Society, Gift of Mary Means Huber, 2009. 330.1>

Fig. 4. Miranda Robinson’s sampler, dated 1839, Saybrook, Connecticut

Courtesy of the Connecticut Historical Society, 1990.142.0>